As I mentioned in the previous post, “‘Pivots’ and Great Powers – Both Sides Now” I thought I should dwell a bit on former Australian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd’s speech/article called “The West Isn’t Ready for the Rise of China” (for the article grab it at the NewStatesman.com). The fact is Rudd – prime minister or not, or foreign minister or not – is one of the smartest foreign policy dudes, especially when it comes to China, in all of the Asia-Pacific.

So what did Rudd say and what did he write? Now the title comes from a quote in the article “It Takes Two to Tango.” It was Rudd himself who drew attention to the quote. It was Rudd’s assertion in his recent Munk School of Global Affairs speech – that closely tracked the New Statesman article – that the quote comes from Mae West. My exploration suggests – “it ain’t so”. Of all the quotes attributed to the famous Mae West no list seems to include that quote. But the quote itself is a reminder of the impact the powers have on each other. More on that below.

So what is Rudd’s basic point? Well it comes from the sub-title. China’s rise to dominance in the international system is, as Rudd suggests, “imminent”. In fact what he actually says is, “… the west is completely unprepared for China’s imminent global dominance”. More pointedly Rudd then poses the key question: we seem unable to determine whether China is prepared to accept the international order the west created over the last 50 years or not. Will China, as Rudd says, “accept the culture, norms and structure of the postwar order? Or will China seek to change it?”:

Importantly, some might say disturbingly, the matter remains unresolved among the Chinese political elite themselves. … At present, there is no centrally agreed grand design. In other words, on this great question of our age, the jury is still out.

While there are some elites in China that favor the continuation of the liberal economic order – obviously those in particular that have benefited from reform and opening – there are political forces in China – conservative political forces and the military – that do not. It is not that they haven’t benefitted from the dramatic sustained economic growth but they certainly are resistant to greater domestic political reform. Moreover, the military – like militaries everywhere adopts hedging and worst case scenario strategies – which raise countermeasures and mistrust in the region and heightens rivalry and competition. The most evident arena of tension recently is the South China Sea but there is tension between China and Japan in the East China Sea. Nevertheless, it remains possible for the west (this is the term Rudd uses but the inclusion of Korea and Japan etc., make this an odd reference) and others, according to Rudd, to have an impact on China’s views and to help China’s leaders to accept a continuation of the current international political order:

Moreover, the rest of the world’s ability to shape the contours of China’s future global role constructively represents a limited window of opportunity, while China’s international debate is still fluid, while Chinese influence continues to be contested, and well before final strategic settings become entrenched.

So Rudd carries a relatively positive message – though clearly not a starry-eyed one. And as he argues, effective engagement with China that retains the liberal order will only come with concerted and collective effort:

But it will require collective intellectual effort, diplomatic co-ordination, sustained political will and, most critically, continued, open and candid engagement with the Chinese political elite.

Rudd has outlined a number of steps for the strategic engagement of China and its elites. But before we get there let me comment on a number of aspects of this analysis that seem to me to raise questions over Rudd’s policy roadmap. First, Rudd’s approach suffers from what I call, “Time Travel”. Though it may be a helpful rhetorical device, I think the notion of China’s imminent global dominance is just wholly exaggerated. Here I am focused on the “imminent”. While China’s dominance in the international political order may come – it is no time soon. There well may be a long period of rivalry and competition but given strategic-military deployments the China “dominance” will for the immediate future remain regional. Which doesn’t mean that engagement of China is not required but it leaves global leadership and influences more fluid and less likely to be dominated by China.

The same “Time Travel” dilemma seems to me to be evident when he examines the emergence of China as the largest economy. Now Rudd admits that it is likely to occur sometime over the next two decades – though he believes that it likely to come sooner rather than later. Fine, but we are still talking some significant time in the future – let’s be optimistic – ten to 12 years. That impacts then on the framing and immediacy of change to the political order and the character of the engagement called for in the global setting. More critically is the reality that real economic power derives from GDP per capita and not just the absolute size of an economy. And China is somewhere in the neighborhood of 100th in GDP per capita. And beyond the low per capita GDP, we should be hesitant to predict China’s economic trajectory from past growth. So while China’s growth has been phenomenal and sustained over thirty years there is still a significant distance to go. And again that impacts on China’s position in the global political order.

On the policy roadmap Rudd believes that the fashioning of China’s engagement necessarily occurs in the Asia-Pacific and where Rudd suggests, “ … the new regional institution underpinned by shared international values will be needed to craft principles and practices of common security and common property for the future.” Now Rudd, to his credit, has consistently over the years urged the need for a broad Asia-Pacific security community. While Prime Minister Rudd promoted the Asia Pacific Community, now he believes that the East Asia Summit (EAS) – from his perspective the successor to the APc – is the appropriate critical setting arraying together all the major powers of the region, including now India, Russia, the US and China, around a single table with, as he describes it, “an open mandate on political, economic and security issues.”

The security dimensions of the EAS and other multilateral settings, however, are contested by China. In the recent ASEAN Ministerials and the ARF meetings China strongly resisted the discussion of the South China Sea territorial disputes, which China has insisted should only be handled bilaterally. The EAS – the summit leaders forum – is just as likely to find China arguing that these disputes should not be included on the leaders’ agenda. Rudd’s comments in Q&A at the Munk School argued that these territorial matters were taken up in any case. Well, they were but at the cost of no communiqué and the discussions at the ministerials say little about the likelihood of placing it on the leaders agenda. It is not the smooth path implied by Rudd.

Multilateral discussions are critical. Engaging China is necessary. But several conclusions can be drawn from contemporary events and behaviors. First, the asymmetry of power with many ASEAN members make the inclusion of most of these states open to division, especially in the context of consensus. Collective effort is important but the critical relationship is the bilateral US-China one. The Australias, Indonesias, Japans and Koreas are significant and can assist in supporting the liberalizing elements within the Chinese system, but it is the engagement of the US that remains critical. If the US-China relationship cannot maintain engagement and a collaborative spirit, I am doubtful the rest can ensure success

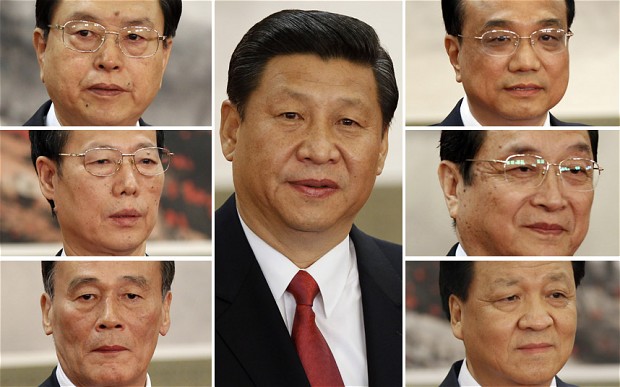

Image Credit: Wikipedia – Kevin Rudd