So it appears just about everyone has joined in. There are of course insightful views of the current global order from some of my IR colleagues, including but not limited to by Thomas Wright at Brookings or Joe Nye at Harvard. But it would appear that many others have joined in as well. And it is understandable. The rise of populist forces, especially in Europe, the surprise election of Donald Trump in the United States and the continuing global economic slowdown, the decline in trade and the incomplete recovery from the financial crisis of 2008 leave an attractive political and economic landscape to contemplate the future of the global order,

This is not to suggest that folks other than my IR colleagues don’t have the necessary insights to assess the implications of current actions and events. Many do. For there is after all a need to assess the political actions, the military capabilities and the economic trends in the global order. And it remains, after all, that it it is still unclear how to determine great power capability, power and dominance. Depending on who you read, it is all about military assets; others suggest it is economic capability; and still others introduce soft power aspects as well. Thus, it is probably not very surprising that as well known an economist as Nouriel Roubini finds he is able to analyze the ‘disorder’ presented by recent events. As he declares in a recent Project Syndicate article :

Today, too, a US turn to isolationism and the pursuit of strictly US national interests may eventually lead to a global conflict. Even without the prospect of American disengagement from Europe, the European Union and the eurozone already appear to be disintegrating, particularly in the wake of the United Kingdom’s June Brexit vote and Italy’s failed referendum on constitutional reforms in December. Moreover, in 2017, extreme anti-Europe left- or right-wing populist parties could come to power in France and Italy, and possibly in other parts of Europe.

What are we to make of all this? Clearly, there is a stunned realization in the Washington beltway that he, Trump, is about to take the helm of US policy. As Maureen Dowd of the NYT acknowledges:

The capital has never been more anxious about its own government. The town is suffering pre-traumatic stress disorder. This guy is really going to be president. … No one knows what is going to happen, but they know it will be utter chaos and that the old familiar ways have vaporized. … The city has the panicked air of a B-horror movie where the townsfolk stand stock still, bug-eyed and frozen, too frightened to flee, waiting for the creature.

And Brookings Thomas Wright has done a good job describing the threads in Trump’s pronouncements that link him to a US foreign policy last seen before World War II. Take the ties Wright draws between Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ announcements and Senator Robert Taft’s pre-war and post war policy pronouncements:

With his background and personality, Trump is so obviously sui generis that it is tempting to say his views are alien to the American foreign policy tradition. They aren’t; it is just that this strain of thinking has been dormant for some time. There are particular echoes of Sen. Robert Taft, who unsuccessfully ran for the Republican nomination in 1940, 1948 and 1952, and was widely seen as the leader of the conservative wing of the Republican Party. Taft was a staunch isolationist and mercantilist who opposed U.S. aid for Britain before 1941. After the war, he opposed President Harry Truman’s efforts to expand trade. Despite being an anti-communist, he opposed containment of the Soviet Union, believing that the United States had few interests in Western Europe. He opposed the creation of NATO as overly provocative. Taft’s speeches are the last time a major American politician has offered a substantive and comprehensive critique of America’s alliances.

And as a result there is a strong attraction by many of today’s commentators to reference through the rearview mirror the interwar policy making, especially US foreign policy making. Analysts are apt to reference the interwar era and to draw the comparisons to that disordered era leading of course to a return to world war. As Philip Stephens of the FT describes: “The history that haunts them is that of the 1930s, when a self-absorbed America stood by as Europe fell to fascism and war.”

Notwithstanding this evident attraction it has to be resisted by any of us evaluating the course of policy making. And for those of us assessing the work of analysts and experts, one should be hesitant to accept analysis that relies on the distant interwar era. That is one of the conclusions to be drawn from Joe Nye’s recent Foreign Affairs analysis of the threats to the Liberal Order in the volume Out of Order:

It has become almost conventional wisdom to argue that the populist surge in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere marks the beginning of the end of the contemporary era of globalization and that turbulence may follow in its wake, as happened after the end of an earlier period of globalization a century ago. But circumstances are so different today that the analogy doesn’t hold up. There are so many buffers against turbulence now, at both the domestic and the international level, that a descent into economic and geopolitical chaos, as in the 1930s, is not in the cards.

Having reflected that this rather facile comparison is inapt, Nye is concerned of the foreign policy direction under Trump:

Increasingly, however, the openness that enables the United States to build networks, maintain institutions, and sustain alliances is itself under siege. This is why the most important challenge to the provision of world order in the twenty-first century comes not from without but from within. … The 2016 presidential election was marked by populist reactions to globalization and trade agreements in both major parties, and the liberal international order is a project of just the sort of cosmopolitan elites whom populists see as the enemy. The roots of populist reactions are both economic and cultural.

As Nye suggests, “Leadership is not the same as domination.” A reflection back on the near past suggests that the failure in part of US leadership is its unwillingness to share leadership in the global order. This is not a “leading from behind” but a real effort to share leadership with other powers in a variety of global governance areas. And it means that others are prepared to step up to aspects of collective leadership. Let’s see if that is possible.

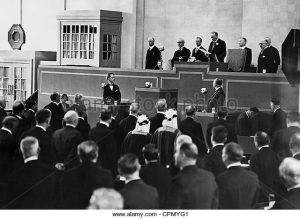

Image Credit: www.alamy.com

The opening of the 1933 London Conference