So let’s stipulate – I like acting like a US lawyer – that the US grand strategy of the second term seems fixed on Asian rebalancing or a ‘Pivot’, and that we have at least some acknowledgement in the halls of Washington that the new grand strategy is as much about economic diplomacy as political and military actions, as I wrote in the last blog post – ‘Determining Who’s On First‘. Well how does this then line up the US-China relationship in the face of new leadership in Beijing? That requires us to look at both the domestic and foreign policy stance of the new leadership.

On the domestic front are we likely to see significant economic and even political reform? On the foreign policy front are we likely to see a more reflective and restrained Chinese strategy in the Asia Pacific in the light of the need to build or rebuild economic alliances and wider collaborative behavior?

Now a quick examination of likely domestic policy moves. First, let’s dispel the impossible. There was little likelihood, asymptotically approaching zero I’d say that these new leaders – from this generation of leaders – would on their own adopt democratic political reform. As China expert Susan Shirk put it recently in the FT.com in the run up to the new Standing Committee choices:

This is a question of legitimacy and popular support for the party,” says Susan Shirk, a US expert on Chinese politics put it ft.com in “China wrestles with democratic reform (November 7, 2012): “They need to show that they’re moving in the direction of democracy but they are very fearful of losing actual control.

So their might be musings of reform – in fact there were such thoughts expressed by some in the old Standing Committee, but actual reform – not likely. To seemingly underscore this, the two candidates most likely to favor political reform – Li Yuanchao the head of the Organization Department (and an early attendee to Harvard’s Kennedy School) and Wang Yang the Communist Party Chief of Guangdong Province – were both left off the Standing Committee. As Iain Mills, a freelance writer in China saw it:

Also of note was the public reappearance of ex-President Jiang Zemin alongside one of the instrumental figures in the Tiananmen crackdown, ex-Premier Li Peng. Although Jiang had taken on the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and secured China’s accession to the World Trade Organization during his presidency, in terms of social and economic policy, the influence of this generation of leaders would seem to be highly retrograde. Jiang loyalists took senior positions in the Central Military Commission, while conservative factions appear to have blocked the promotion of reform-minded officials such as Wang Yang.

Okay so little likelihood of serious political reform. But what of significant economic reform. Certainly the previous leadership including Premier Wen Jiabao pointed to the need to tackle the growing economic power and corruption of China’s State-owned Enterprises. Now of course The Premier only began to talk about this at the twilight of his career. And it would appear that the collective message, including from the new Chairman Xi Jinping, is a broadly anti-corruption message. Unfortunately this message is conservative and not reformist. The anti-corruption message is an internal Party message to root out bad guys -if they can be found – and not indicative of major structural reform. Again Iain Mills reflections on economic reform seems apt:

It should also be noted that the renewed pre-eminence of conservative elements on both the Standing Committee and the Central Military Commission comes ahead of potential changes of the heads of key civilian institutions including the People’s Bank of China, the state-run power sector and the National Social Security Fund. How these institutions will be aligned and function under the new administration remains unclear. The broader picture, however, seems one of an economic reform agenda that will continue at a gradual pace, while hopes of major political reform have been pushed out to 2017 at the earliest.

Finally, what then of foreign policy action? Now it was positive that the new Chairman took over the the Central Military Commission. It is evident that foreign policy has suffered from a number of voices. China’s behavior in the Asia Pacific has seemingly become more assertive. The pattern has yet to end. A new policy to take effect on January 1st provides that border patrol police will have the right to board and expel foreign ships entered disputed waters in the South China Sea. China has also begun to issue new visas that includes a picture including disputed territory in the South China Sea. Various South China states including the Philippines and Vietnam have publicly objected to the new visas and refused to validate them. Officials seem to be continuing policies that reflect the assertive China strategy in the South China Sea, not to mention the East China Sea. In the face of little moderation, China policy, as described by Mills, appears to continue to be an assertive nationalist approach:

Beijing has often been unable to speak with one voice on major external events and has offered no clear articulation of how it would operate as the largest power in Asia. This vacuum, coupled with still-fervent nationalist sentiment in many quarters, appears to have been filled by those who favor a more forceful approach to enforcing China’s foreign policy objectives.

The assertive China approach has driven a number of ASEAN states to encourage a US return to Asia; it has even enabled Japan to play the military card with a number of Asian players. There is little to hinder the new leadership if it chose to moderate its stance in the Asia Pacific. Let’s watch closely for a more collaborative China approach of the new China leadership.

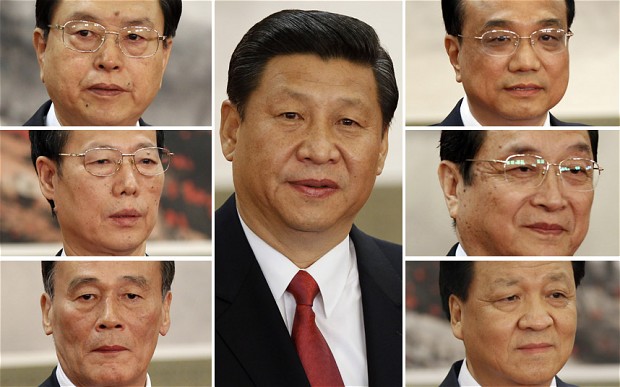

Image Credit: Reuters