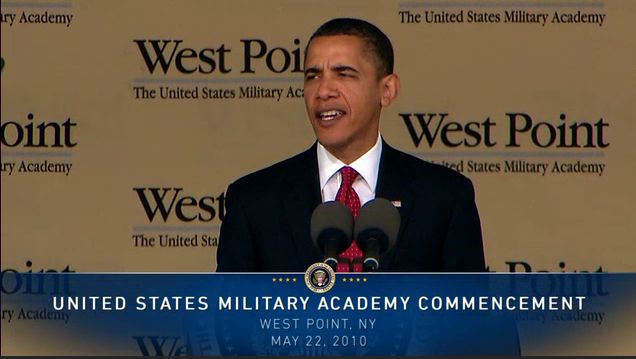

Now evidently – from the image above – this is not the first speech that US President Obama has given at West Point. Here then is an earlier portrait of the President there – the black hair obviously is a dead give away. Still the President’s commencement address this year has been seen as an opportunity for the President to outline his Administration’s foreign policy and the rationale in how he and his officials have implemented US foreign policy.

In the last months there has been much criticism over the President’s unwillingness to act in Syria, to be unwilling to provide the new Ukrainian government with greater military support, and on and on. There have been allusions to American “fecklessness” by those in Congress, e.g. John McCain and Bob Corker for two examples, and in the commentariat as well. Many have criticized the President’s “haste” in ending the Iraq and Afghanistan interventions, and on and on.

So here was a platform to respond to all that. What better venue than US Military Academy and in front of the newest graduating class. Now one might hope that the President might be drawn to extend beyond the military, say to a graduating class of diplomats or international policy analysts, as an additional venue to explicate US foreign policy. But even with the President pushing back against the haste to exercise the military option, it would be hard not to see the intimate link between military power and US foreign policy.

Now first to context. There has been much hoopla over the return of geopolitics. Numerous observers have hinted at the emergence of Cold War II with the “bare knuckle” actions of the Russians in the Ukraine. And the Chinese have been criticized for recent actions in the South China Sea. Even though unwilling to adopt fully this return of geopolitics, Tom Friedman today couldn’t resist indulging his view over the recent US and Russian actions in the Ukraine in his op-ed “Putin Blinked“:

The crisis in Ukraine never threatened a Cold War-like nuclear Armageddon, but it may be the first case of post-post-Cold War brinkmanship, pitting the 21st century versus the 19th. It pits a Chinese/Russian worldview that says we can take advantage of 21st-century globalization whenever we want to enrich ourselves, and we can behave like 19th-century powers whenever we want to take a bite out of a neighbor — versus a view that says, no, sorry, the world of the 21st century is not just interconnected but interdependent and either you play by those rules or you pay a huge price.

Now having spent some time working through 19th century international relations recently, and I am not quite sure what Friedman is referring to – certainly not the concert diplomacy that dominated in the post Napoleonic period for at least several decades and reemerged with the Bismarckian Concert in the 1870s for close to two decades. The point is it is not just interconnectedness or interdependence that suggest restraint and operation by rules and the avoidance of unilateral action.

Now Stephen Walt, again today, makes no references to earlier centuries and strategies in his recent FP piece. I suspect for Walt – wearing his comfortable “Realist hat” – that global politics remains much as it has in the classic days of great power politics. There is no return because it never went away. Walt never fails to mention the security of the US position given its domination of the western hemisphere.

Although he seems to have recognized from the start that the United States had to reduce its global burdens in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the debacles in Iraq and Afghanistan, neither Obama nor his advisors ever managed to articulate and stick to a set of core strategic principles. The result has been an overly ambitious foreign-policy agenda that kept top officials busy but failed to produce significant positive results. … What does he regard as the most pressing threats to U.S. security? Where are the most promising opportunities that, if seized, would make ordinary Americans safer or more prosperous? What issues or problems should the United States focus on, and what issues or problems can be downgraded or deferred?

Now it is fair to say, just as Walt suggested, that Obama doesn’t provide us with “core strategic principles” or a list of the “most pressing threats to US security”. In fact I was nonplused by his short shrift of Asia Pacific in this speech. There is just one bow to the effort to encourage a Code of Conduct between ASEAN and China, but that’s pretty much it. If this a ‘pivot’, you could sure fool me. But maybe that’s the point.

But then Obama helpfully expends a fair bit of time looking at the means for exercising American influence. First up, the use of military power – at least for what he describes “when our core interests demand it.” And not surprisingly he sees terrorism as “the most direct threat to America, at home and abroad …” And the quotable line is:

Here’s my bottom line: America must always lead on the world stage. If we don’t, no one else will. The military that you have joined is, and always will be, the backbone of the leadership. But US military action cannot be the only – or even the primary – component of our leadership in every instance. Just because we have the best hammer does not mean that every problem is a nail.

So far not much new though I love that last line. But then the President turns to what he calls “the third aspect of American leadership and that is our effort to strengthen and enforce international order.” So the President turns to multilateral action. And what he says is:

In each case, we built coalitions to respond to a specific challenge. Now we need to do more to strengthen the institutions that can anticipate and prevent problems from spreading.

Now it is unfortunate that the President falls back on the traditional formal institutions in the main , the UN, NATO and even international law – that is his reference to the Code of Conduct. He doesn’t reflect at all on the possibilities for the G20, EAS, whatever. And then a reminder that what applies to others also applies to the United States:

I believe in American exceptionalism with every fiber of my being. But what makes us exceptional is not our ability to flout international norms and the rule of law; it is our willingness to affirm them through our actions.

As a means then multilateralism and adherence to the international norms and the rule of law. I do not underestimate the consequence of the President calling on US leadership to forge a path through multilateralism and collective action.

But how?!

The difficulty for some time now is the US inability to articulate let alone exercise multilateral behavior. If it is a shift to concert diplomacy there is no roadmap.

Image Credit: Washingtonnote.com