Nova Délhi – Índia, 29/03/2012. Presidenta Dilma Rousseff posa para foto junto com os Chefes de Estado do BRICS. Foto: Roberto Stuckert Filho/PR.

[Editorial Note: This piece was originally posted at the RisingPowersProject at the inauguration of this new site.]

So the Hangzhou G20 Summit has come and gone and now the eighth BRICS leadership conference hosted again by India, but this year in Goa as opposed to the previous India BRICS Summit in New Delhi is just about upon us. This BRICS Leaders’ Summit will take place on October 15th and 16th.

So where are we in determining the the state of global order leadership and the Liberal Order that has been so prominent since the end of the Cold War? A sweep of editorials and reviews of China’s G20 in Hangzhou has been notably downbeat. At this site ‘Rising Powers in Global Governance’, my colleague, Jonathan Luckhurst described the Hangzhou reviews this way: “The Group of Twenty (G20) has received poor reviews in recent years, so expert reactions to the Hangzhou G20 Summit of September 4-5, 2016 were hardly surprising.”

While it is evident that recent G20 Summits, Australia, Turkey and now China, have not seen significant progress or stellar outcomes, the Hangzhou summit is of a slightly different character. The hosting by China was viewed with much anticipation by experts and observers. Here, the largest of the large emerging market countries was taking the helm of what is arguably the most important global leadership forum in global governance. China is also the evident Rising Power and potential ‘challenger’ to US global leadership, or at least leadership in Asia, and China was for the first time preparing to host this key global institution. After all, the almost twenty countries represent about 85 percent of world production, 80 percent of global trade and about two-thirds of global population.

But caution needed to be exercised by those awaiting with great expectations the Chinese Presidency. On the G20 front it has been evident, and commented for some time now, that the G20 has very imperfectly transitioned from a ‘crisis committee’ – at the time of the Great Recession – to a ‘steering committee’ trying to drive the global economy forward. In fact the challenges facing the global economy today really hinder that transition. And further, I would suggest that the failure is not about a wide remit versus a narrow one for the G20. The reality. There is nothing more difficult in global governance than to lead states with an agreed global macroeconomic policy; to drive growth or restrain other global economic maladies such as a variety of imbalances.

The failed efforts are numerous. The initiatives at the Brisbane Summit only underscore, if it needed to be, the contemporary difficulties. As my colleague Mike Callaghan, the former program director of the G20 Studies Centre at the Lowy Institute in Australia (2012-2014), and a former Australian Treasury official has made clear in private conversations, the growth agenda is largely secured at the national level. As the Brisbane Action Plan made clear, efforts to grow the global economy are anchored in domestic policy initiatives. And attitudes are hardly in harmony over what must be done. The result is another example of a collective effort to boost global economic growth that falls short due to national disagreement, legislative opposition or other domestic factors.

Moreover. hosting proved to be a formidable effort and one I am not sure Chinese officials were prepared for in the runup to the Summit. It was their first G20, though they have organized major summits in the near past such as APEC. I am told, nonetheless, that the host came with significant game plan only to find that countries were in no way willing to just ‘fall in line’ with Chinese proposals. So, while China could provide a ‘good show’ in Hangzhou, producing the coordination, let alone policy harmonization, was another matter altogether. What can I say – for China it was all part of the socialization process in coordinated global leadership.

Then too the context of global economic growth was far different than what it had been in the near past. At the time of the Great Recession the major ‘hit’ was felt by the established countries in Europe and the United States in particular. It appeared as the rising economies were likely to be able to avoid the immediate recessionary impacts. But since then BRICS countries such as Brazil, South Africa and Russia (though not India), and for a variety of reasons, they have suffered significant economic declines. Even China the first among all these BRICS countries experienced a rapid economic deceleration though it would appear that China’s economic growth has stabilized.

Chris GIles, in the FT penned earlier in the week an article,”Global economic growth ‘sliding back into the morass’”, anticipating the upcoming IMF fall meetings. As he described the atmosphere for the upcoming fall IMF meetings:

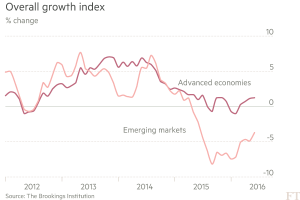

Hanging over the meetings is the fear that the failure to improve living standards in advanced and emerging economies was important in the UK’s vote to leave the EU, may propel Donald Trump to the US presidency and will strengthen the hands of populists such as Marine Le Pen in France. As can be seen from the latest economic data, in this case, the latest update of the Brookings-FT Tiger index, the emerging market countries suffered a serious economic decline. According to Eswar Prasad and Karim Karim Foda at Brookings the data, “presents a picture of general despondency in the global economy that more than offsets isolated signs of strength in some economic indicators in a few countries.” So, the economic impact has been felt in the advanced countries especially with strong anti-globalization political movements. Brexit was one political consequence; we await November 8th in the United States to see whether an anti-globalization populist takes the reins in Washington. As many of my colleagues suggest, such an outcome could result in deep wounds to the Liberal Order as we know it. It could spell the end, at least for a time, of any effort to enhance global economic coordination.

On the brighter side, whereas it appeared to some that the formation of the BRICS was a signal of a new order, an order, possibly in opposition, to the dominance exercised by the West, especially the United States, this does not appear to be the case. There is no question that at the time of the Great Recession these rising powers, especially China, pressed for a more realistic distribution of influence in the formal institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank. These efforts, at least partially successful, do not seem to be the opening steps in a challenge to the current Liberal Order. And while some reshuffling has occurred at the formal institutions and the emerging powers have created a number of new institutions such as the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), and China’s Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank (AIIB) the challenge to the Liberal Order appears quite muted. Moreover, it doesn’t appear that the norms and rules of the Liberal Order are being challenged collectively or singularly.

The annual meetings [of the IMF], according to Chris Giles “will encourage policymakers to pursue inclusive and faster global growth as international organisations, finance ministers and central bank governors seek to reassure the public they can co-operate and that they have the necessary tools to break five years of economic disappointments.”

In an odd way then this observation by Chris Giles is something of a hopeful sign. And Germany may, but only may, pick up on this. The politics in Germany, not to mention elsewhere in Europe, or possibly, and pessimistically the United States, could well lead to an even longer period without global leadership.