This Post is a collaboration with Yves Tiberghien Professor of Political Science at UBC and RisingBRICSAM blogger Alan Alexandroff.both Principals at the Vision20. It underscores that key actors in Asia, Europe and elsewhere are not waiting on the United States to return to global collaboration and multilateral action.

Out of Asia there is a major push on various global governance fronts. The world is not waiting for the United States. And in fact Joe Biden, the President Elect and his people are going to have to think ‘hard’ about whether they are prepared to be ‘left behind’ in the march forward of various multilateral gatherings. Are the demands of domestic politics and the Democratic Party’s distaste for ‘free trade arrangements’ going to leave the Biden Administration lukewarm to rejoining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership or CPTPP? Lukewarm leaves the United States on the outside of efforts to integrate trade and investment in Asia and beyond.

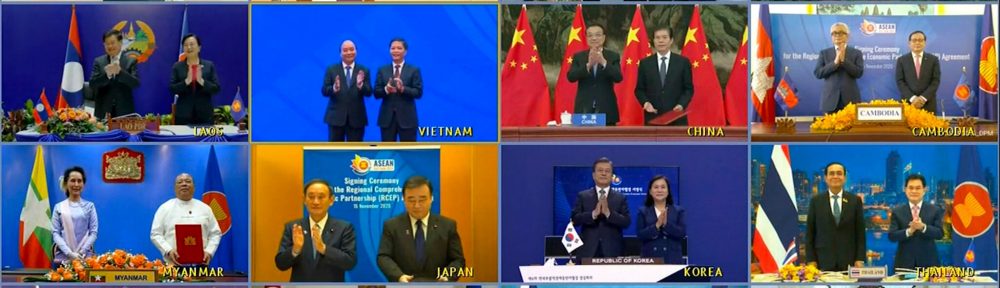

While the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a limited integration of trade and investment, nevertheless the RCEP is the largest regional agreement concluded in Asia. The Pact covers 2.2 billion people and 15 countries . It includes China and other major economic actors including Japan and South Korea. As the NYTimes (2020) points out:

The pact will most likely formalize, rather than remake, business among the signatory countries. Its so-called rules of origin will set common standards to determine whether a final product qualifies for duty-free treatment, potentially making it simpler for companies to set up supply chains in several different countries.

While the RCEP lacks significant and needed steps to further liberalization and common regulation in key areas such as services trade, e-commerce, intellectual property protection and the elimination of manufacturing subsidies it is a key advance for the Asian region. As pointed out by Yves Tiberghien (2020) in a just published EastAsiaForum post:

RCEP will advance the acceleration of regional economic integration in Asia, and pushes back on Trump’s strategy of decoupling of US allies from China. While Southeast Asian countries, Japan, South Korea, and Australia may all be wary of China at the moment and seek diversity in their trade relations, they simply cannot sustain their prosperity without stabilisation of trade relations with China. Asia is criss-crossed by ever intensifying value chains, and China’s still an integral part of that. Vietnam and other ASEAN countries are rising as manufacturing hubs, but that’s a process accompanied by increased imports of intermediary goods from China.

But RCEP is also of global significance. The agreement, signed off in the middle of a pandemic and US–China trade war, reminds the world, first, that East Asia countries, unlike the Americas and Europe, have broadly succeeded in controlling COVID-19. That success, across different types of political regime, with a similar respect for science, expertise, and trust in government, was accompanied by general acceptance of mask-wearing and community rules.

Second, it also reminds the world that the biggest trading group in the world economy is doubling down on the rules-based multilateral system. Research by Homi Kharas shows that most of the increase in the global middle class until 2030 will take place in China and Asia.

RCEP also embeds the first trilateral agreement between China, South Korea and Japan, itself a huge deal. The common interests of these three countries have over-ridden tense geopolitical relations across the Asia Pacific. RCEP underscores the pragmatic efforts of Japan to balance its strong security stance on the South China Sea and in the East China Sea with stability in the bilateral relationship with China. After the completion of the CPTPP, the EU–Japan partnership, and the US–Japan agreement, this marks the completion of the Abe trade agenda (even though Japan would have preferred India to join RCEP). …

As well, RCEP brings significant institutionalization to Japan’s economic relations with China, including a new chapter on e-commerce (with a ban on data localisation requirements), rules on government procurement, and rules on intellectual property rights that go beyond WTO rules. The same calculations drive Australia’s readiness to sign RCEP in the midst of a bitter, but hopefully short-lived, trade fight with China.

The coming Biden Administration needs to rethink its reluctance to rejoin the CPTPP. If it fails to do this it could be on the outside of growing multilateral economic integration and possibly more.

Image Credit: Vietnam News Agency, via Associated Press.