Great power rivalry has forcefully reappeared. It is a jolt for anyone that follows international governance to watch the Russian actions in the Crimea and to hear the assertions and rationalizations by Russia’s President Putin concerning Russian annexation of the Crimea.

Many observers witnessing all this have declared an end of an era – the closing out of the post cold war era that saw the United States emerge as the sole superpower. It appears that US leadership is being tested in a number of conflict arenas. David Sanger, the NYTs chief Washington correspondent recently declared (“Global Crises Put Obama’s Strategy of Caution to the Test” NYT March 16, 2014):

In short, America’s adversaries are testing the limits of America’s post-Iraq, post-Afghanistan moment.

We’re seeing the ‘light footprint’ run out of gas,” said one of Mr. Obama’s former senior national security aides, …

Is it Mr. Obama’s deliberative, pick-your-battles approach that is encouraging adversaries to press the limits? Or is this simply a time when exercising leverage over countries that defy American will or the international order is trickier than ever, and when the domestic pressure to stay out of international conflicts is obvious to overseas friends and foes alike?

It is almost certainly some combination of the two.

Judah Grunstein, the editor-in-chief of World Politics Review , March 17, 2014 “Diplomatic Fallout: The European Union’s Bait-and-Switch in Ukraine” has underlined that Putin’s Russian actions in Crimea have wounded collective great power efforts:

Though undeclared and unopposed, Russia’s invasion of Crimea has now reintroduced the specter of great power aggression and armed conflict in the heart of the Eurasian space. There is no compelling reason for the U.S. or its European allies to consider defending Ukraine’s territorial integrity with force. But the failure to consider the possibility of armed conflict in defense of other post-Soviet European allies would today amount to strategic malpractice. In pressing his tactical advantage in Crimea, Russian President Vladimir Putin has thus simultaneously highlighted the receding limits of American hegemonic power undergirding the global order and the chimera of the rules-based global governance system that had been slated to replace it.

So where to from here? Back in 1995 Professor John Kirton, one of the earliest observers of the rise of global governance – notably the emergence of the G7 and later the G8 – from right here at the University of Toronto argued that:

the G7 system of institutions is the late twentieth century global equivalent of the Concert of Europe that helped produce peace among the great powers, and prosperity more widely, from 1814 to 1914.

While it is arguable whether the two institutional structures are equivalent, nevertheless the G7 and the G8, and now the G20 as well, do reflect contemporary great power concert settings. Now few observers today use the terminology of “concert”. But all these institutions are initiated to promote collaboration among todays self-declared great powers in global economic policy making at least and possibly in global security as well.

The West – here Europe and the United States – imagined that by reaching out this “deformed” but western country could join what Mikhail Gorbachev identified as the “the common European home”. Anne Applebaum recently suggested in a piece in Slate that with reform in its economic policy making and its adherence to various institutions Russia would become part of the West:

In the 1990s, many people thought Russian progress toward that home simply required new policies: With the right economic reforms, Russians will sooner or later become like us. Others though that if Russia joined the Council of Europe, and if we turned the G-7 into the G-8, then sooner or later Russia would absorb Western values.

Instead western leaders after Crimea, according to NYT‘s Ross Douthat, need to assess that Russia, at least under Putin, is:

But it [Russia] is a geopolitical threat — a revisionist, norm-violating power — to a greater extent than any recent administration has been eager to accept.

How can these contemporary concert settings deal with at least the “rogue-like” behavior of this great power and in particular the leadership of Russia’s President Putin? Clearly Russia’s current behavior precludes a collective security-like behavior. As US national security advisor, Susan Rice declared NYT:

Russia’s integration into the global political and economic order after the Cold War, Ms. Rice said, was predicated on its adherence to international rules and norms. “What we have seen in Ukraine is obviously a very egregious departure from that,” she said.

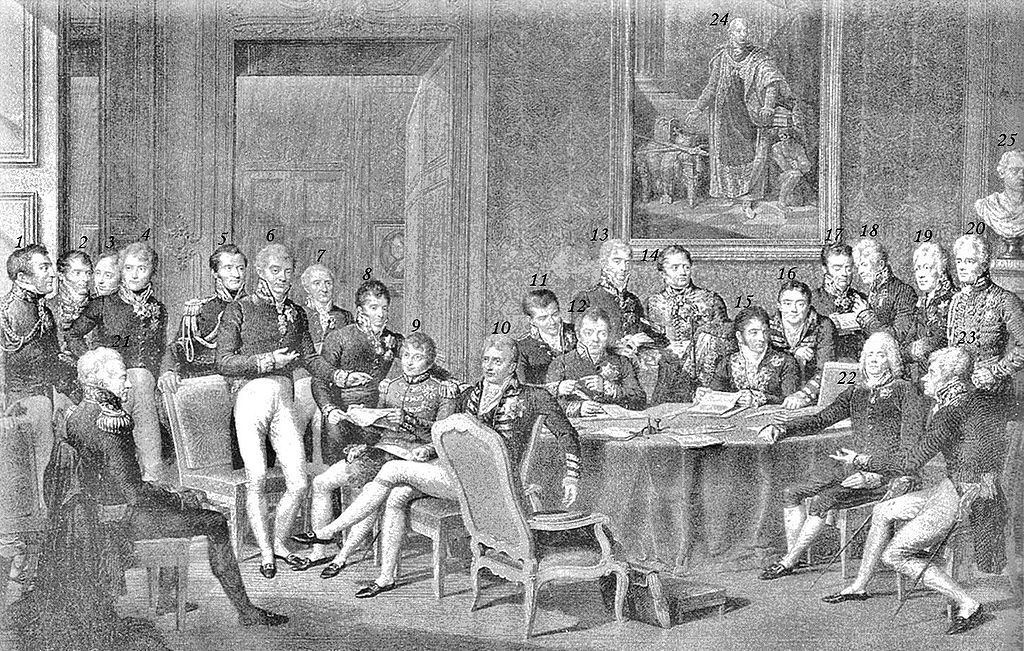

But let’s cast our gaze back for just a moment to the 19th century concert behavior. First there were in fact two concert structures that sought to maintain peace and international stability in the period. There was of course the Concert of Europe formed following decades of conflict with Napoleon. The 5 major powers having defeated finally Napoleon sought to act as a collective body and importantly to restrain their own impulses to act unilaterally. They built a great power collective structure to secure peace and international stability.

Today one of the great powers is acting in exactly the manner that this Congress of Europe was designed to preclude. The Concert of Europe unfortunately cannot be very helpful here. Observers would acknowledge, however, that this Concert of Europe failed to outlast the revolutions of 1848. However, this does not end the story of concert behavior in Europe in the nineteenth century. Though often ignored, a second concert period arose following the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian conflict. This second concert period was largely the product of the very person that had brought on great power conflict in the first place – that is Germany’s Chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

This Bismarckian concert was constructed on a complex series of alliances. But the basic elements were clear – collective behavior and restraint on the part of all the great powers of the time, just as before in the Concert of Europe but without France. Bismarck collected potential adversaries such as Russia and Austro-Hungary and Russia and Great Britain bound them in a concert-like structure but isolated out the one aggrieved great power, as Bismarck saw it – France.

Obama, and now most critically Germany’s Merkel have returned to a G7 leaders format. First the G7 leaders have suspended preparations for the G8 Summit that was to be hosted by Russia in June. The G7 leaders will meet for the first time in a very long spell at the margins of the Nuclear Security Summit, which is scheduled to take place next week in the Hague. This G7 leaders meeting apparently will focus on what additional steps the G7 leaders can take to respond to Russia’s actions in the Ukraine. So here is an effort to forge collective action but isolating at the same time Russia.

The next step is the G20. Can Obama build concert action in the G20 without Russia? Let’s see.

Image Credit: The Congress of Vienna – Wikipedia.org