At least with respect to the Philippines, China may decide to raise the pressure. As Keith Johnson and Dan De Luca argued:

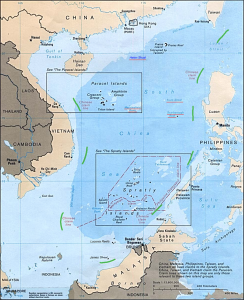

China could also ratchet up the fight with the Philippines by carrying out dredging and reclamation work at Scarborough Shoal, one of the features close to the Philippine coast and a reef at the center of the spat between the two countries. Or China could even try to blockade Philippine marines currently stationed at one of the tiny atolls, potentially threatening a showdown with the United States, which has a mutual defense treaty with Manila.

China could of course express its displeasure beyond just the Philippines. China might raise an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), as apparently some have urged in the PLA, and as China did over the East China Sea. Or China might renounce UNCLOS altogether. On the other hand China might determine to lower the temperature in the South China Sea. In the best of circumstances, and offered up by former Australian Foreign Minister Gareth Evans, now the head of the International Crisis Group, China could take temperature-lowering steps:

These steps include a halt to overtly military construction on its seven new artificial islands in the Spratlys; not starting any new reclamation activity on contested features like the Scarborough Shoal; ceasing to refer to the “nine-dash line” as anything other than a rough guide to the land features over which it continues to claim sovereignty; submitting these claims at least to genuine give-and-take negotiation, and preferably to arbitration or adjudication; advancing negotiations with ASEAN on a code of conduct for all parties in the South China Sea; and an end to dividing and destabilizing ASEAN by putting pressure on its weakest links, Cambodia and Laos, on this issue.

It would appear to many experts, according to Keith Johnson and Dan De Luca in the FP that “the ruling presents Beijing with a pivotal decision”. And China’s actions and the reactions from the region, especially from the regional ASEAN, or Japan and of course the United States could raise or lower international stability in the global order.

But perhaps the most interesting comments arise from experts that think in broader geopolitical terms. For them the answer is obvious – great powers are unwilling to be bound by international law. International law is for the smaller powers but not great or rising powers like China. Harvard’s Graham Allison is one of those experts. Steeped in great power diplomacy and global order, Allison described China’s behavior at The Diplomat in an article entitled, “Of Course China, Like All Great Powers, Will Ignore an International Legal Verdict” this way:

It may seem un-American to ask whether China should do as we say, or, by contrast, as we do. But suppose someone were bold enough to pose that question. The first thing they would discover is that no permanent member of the UN Security Council has ever complied with a ruling by the PCA on an issue involving the Law of the Sea. In fact, none of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council have ever accepted any international court’s ruling when (in their view) it infringed their sovereignty or national security interests. Thus, when China rejects the Court’s decision in this case, it will be doing just what the other great powers have repeatedly done for decades. …

Observing what permanent members of the Security Council do, as opposed to what they say, it is hard to disagree with realist’s claim that the PCA and its siblings in The Hague – the International Courts of Justice and the International Criminal Court – are only for small powers. Great powers do not recognize the jurisdiction of these courts – except in particular cases where they believe it is in their interest to do so. Thucydides’ summary of the Melian mantra – “the strong do as they will; the weak suffer as they must” – may exaggerate. But this week, when the Court finds against China, expect Beijing to do as great powers have traditionally done.

And Allison was quick to point to earlier equally dismissive behavior by the United States:

Thirty years ago, a similar international panel ruled against the United States in a case concerning the mining of harbors in Nicaragua. Washington ignored the ruling, and saw its international credibility take a big hit.

Let me beg to disagree with this thoroughly realist perspective described by Allison. What Allison presents is a global order thoroughly defined by ‘power’ – the great powers balance and the smaller powers either balance or bandwagon as the case may allow or necessitate. International law, in such a power dominated global order is mere epiphenomenon quickly cast aside as are other well-meaning but ‘powerless’ norms and rules that merely hamper great power behavior. The most evident recent behavior to match this great power presentation was the violation by Russia of Crimea and Crimea’s forcible removal from the Ukraine – a clear act of ‘might makes right’.

But the international system is far more complicated than the picture presented by Allison, I would suggest. While ‘power’ actions evidently do take place, today’s global order is not just a ‘power’ defined governance system. Norms, rules and laws do shape and importantly restrain great power behavior. Maybe not all the time but more often than realists suggest.

Today’s global order is not just one built on power, as in the 18th century, or in fact far earlier as Allison would have us believe with his reference to Thucydides.

Image Credit: By International Court of Justice; originally uploaded by Yeu Ninje at en.wikipedia. – International Court of Justice 60th Anniversary Press Pack; transferred from en.wikipedia by Smooth_O using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4395631

Image Credit: By U.S. Central Intelligence Agency – Asia Maps — Perry-Castañeda Map Collection: South China Sea (Islands) 1988, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17066897