So, the Summit for Democracy has come and gone. Much commentary preceded, accompanied, and then followed this December 9th and 10th gathering. Truth be told there is a continuing stream of observations still. Various countries openly applauded the Summit though unsurprisingly those uninvited pushed back starkly including in the case of China holding a conference of many of the uninvited.

So, the Summit for Democracy has come and gone. Much commentary preceded, accompanied, and then followed this December 9th and 10th gathering. Truth be told there is a continuing stream of observations still. Various countries openly applauded the Summit though unsurprisingly those uninvited pushed back starkly including in the case of China holding a conference of many of the uninvited.

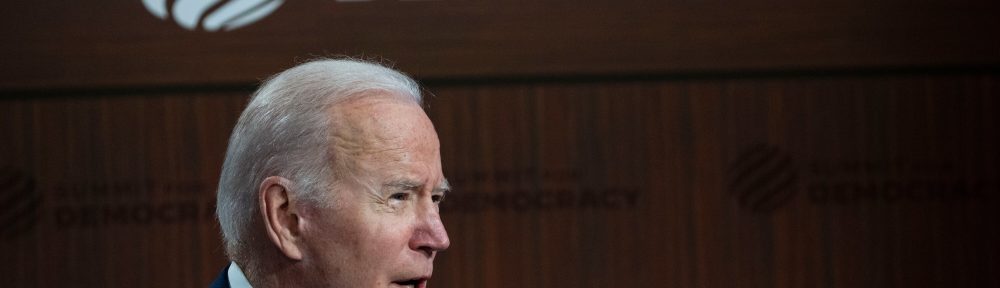

The lingering question for the global order and its key participants remain: what does this Summit announced early on by then presidential candidate Joesph Biden tell us about current US foreign policy; what is Biden’s strategic policy framework particularly in relationship to China and Russia – the two most evident rivals and authoritarian states; and what is the conclusion drawn by close US allies and partners? What has been gained; what has been hindered and harmed?

The lack of clarity over the purpose of this Summit is fairly evident. This Administration has left seemingly a variety of presumed goals ‘on the table’. It appears in fact as though the Administration identified at least three goals: an anti-corruption initiative; a protection of human right and more broadly a protection of democracy; and an autocracy versus democracy foreign policy approach, presumably part of a US democracy promotion goal.

On the democracy protection front the Administration offered a number of policy initiatives, including funding: As President Biden identified these efforts in his opening remarks:

Working with our Congress, we’re planning to commit as much as $224 million[$424 million] in the next year to shore up transparent and accountable governance, including supporting media freedom, fighting international corruption, standing with democratic reformers, promoting technology that advances democracy, and defining and defending what a fair election is.

This initiative was part of the US effort to encourage all participants to set goals and report back in a follow up on these commitments. As the President expressed it:

… and to make concrete commitments of how — how to strengthen our own democracies and push back on authoritarianism, fight corruption, promote and protect human rights of people everywhere. To act. To act. This summit is a kick-off of a year in action for all of our countries to follow through on our commitments and to report back next year on the progress we’ve made.

Still the clarity surrounding the Summit was never very evident to most. Indeed there appears to be no agreement on the nature of the declared initiatives . Observers have taken the above to be democratic promotion and not protection. This multiplicity of goals and their accompanying confusion have enabled experts, officials and commentators to choose their own goal from the menu of options offered by the Administration. Ben Judah at the New Atlanticist described one view of the Summit:

The event offers a critical new approach to fighting corruption by focusing on democracy protection, rather than democracy promotion, taking the approach of fixing your own house first.

Well maybe, he’s right, but others suggest exactly the opposite with the primary objective for the gathering to be democracy promotion. Without clarity from the Administration the dominate narrative became far too frequently who was invited and who was not. This became the favorite spectator sport for commentators and observers participants and not.

Furthermore, the Summit gathering led to a strong pushback from leading authoritarian states in the global order – and therefore not invited, particularly Russia and China. Their ambassadors to the United States published a rare joint opinion in the National Interest that, as emphasized in China’s Global Times underscored that the gathering was “an evident product of its Cold-War mentality,” which will stoke up ideological confrontation and lead to a rift in the world, creating new “dividing lines.” But the leading authoritarian state, China didn’t just stop there. In fact it organized, as described by NPR a dialogue and then issued a defense of China’s ‘democratic’ system:

In addition to the dialogue, China’s State Council, or cabinet, released a 30-page white paper over the weekend entitled, “China: Democracy That Works.” The Foreign Ministry followed with its own report blasting the state of U.S. democracy. And state newspapers have run countless editorials extolling China’s system and questioning America’s.

What can one conclude from the Summit with respect to two global order concerns: the impact on US allies and partners; and the the consequences for US-China relations?

With respect to allies its impact possibly may be known in a year as we watch efforts to advance country commitments on democracy protection. On the other hand, the Summit may have only turned the spotlight more directly on the US and the evident democratic backsliding in the country and its politics. As Michael Crowley and Zolan Kanno-Youngs wrote in the NYTimes:

But while the administration may have viewed the promotion of democracy as an easy way to firm up alliances and partnerships, which Mr. Biden has said were badly damaged under his predecessor, Donald J. Trump, the event has become a focus of criticism from around the world, as well as from U.S. activists concerned about the fissures within America’s own democratic system.

Deep concerns have been expressed by allies at the very troubled state of US politics. There is evident nervousness over the prospect of another Trump presidential run and what that means for alliances. Underscoring the continuing concerns, notwithstanding a generally positive view from colleagues from Brookings, Norman Eisen, Andrew Kenealy and Mario PIcon they suggested:

… it laid a robust groundwork for success despite some skeptical and even pessimistic examinations of the challenges it faced. The summit has already resulted in some initial measurable commitments to advance democracy in the U.S. and abroad, establishing specific, concrete steps to fulfill them. But now there must be vigorous follow through by the United States, other participants, and in particular civil society for the Summit’s proposed “year of action” on democracy at home and abroad before it reconvenes next December. …

So, allied concerns have not seemingly been allayed. What then of the impact on geopolitical tensions especially between the US and China. Clearly, the autocracy versus democracy framing does nothing to improve the prospects of collaborative multilateral efforts. As Stewart Patrick and Ania Zolyniak wrote for the Council of Foreign Relations in the The Internationalist:

The framing of the gathering—a summit for democracy—reflected Biden’s thesis that the contest between democracy and authoritarianism “will define our future”—requiring the world’s free, open societies nations to stand by one another in this moment of peril.

Among the most common critiques was that the summit would divide the world into two camps, democratic and authoritarian, complicating cooperation on shared challenges. On closer examination, this charge loses some of its potency. To begin with the world is already divided, a reality that cannot solely, or even primarily, be blamed on the United States and its allies. It is the product of a conscious effort by Beijing, Moscow, and other authoritarian governments to promote an alternative world order to the open, rule-bound international system the West has championed, by and large, since 1945.

Though it well may be there are tensions and divisions already in the global order as described above, it is not a potent reason to frame global order relations in an ‘us-versus- them’ frame that only heightens the divisions and undermines collaboration. Moreover, as the EAF editorial board makes clear there is little if any appetite for joining this political order framing among potential allies and partners. In what the US has made clear recently is a vital region for US global order, the Indo-Pacific world, there seems to be no appetite for geopolitical divisions envisaged by this Administration:

The message that sends is clear: ASEAN has no interest in any new paradigm of regional security that neglects economic development and cooperation, or that subordinates it to strategic rivalries between competing hegemons. While ASEAN’s members will continue to engage with China and the United States in a manner that accords with their own national security objectives, those objectives themselves will be in the service of a broader conception of regional diplomacy that prioritises economic development and openness, not geopolitical rivalry.

While US democracy protection or promotion appears to be an important aspect of this Administration’s foreign policy there is a need to listen to partners and competitors alike. Those voices seem to be saying something significantly different than Biden and his Administration.

And oh by the way – Seasons Greetings and Happy Holidays! see you in the new year.

Image Credit: SWAP-videoSixteenByNine3000