Many anticipated, and or feared, the flood of Executive Orders from the second Trump White House these past weeks. The barrage of Executive Orders follows a playbook conceived from a longtime Trump supporter Steve Bannon. Bannon referred to it as ‘flood the zone’. Bannon served as the White House’s chief strategist for the first seven months of U.S. president Donald Trump’s first administration, before Trump discharged him. He remains a strong supporter of Trump actions. As Luke Braodwater of the NYTimes describes this Bannon approach:

… Bannon boasted of the ability to overwhelm Democrats and any media opposition through a determined effort to “flood the zone” with initiatives.

On Tuesday, just when Democrats thought they might come up for air, news broke that Mr. Trump had ordered a freeze on trillions of dollars in federal grants and loans, prompting a new round of outrage.

It is a little unclear how adept the Democrats are in parrying the ‘flood the zone’ approach but there does seem to be some awareness of the tactic:

“It’s a little bit like drinking from a fire hose,” Representative Gerald E. Connolly of Virginia, the top Democrat on the Oversight Committee, said of the pace of Mr. Trump’s moves. But he said that speed is likely to cause sloppiness and mistakes.”

They’re going to stumble,” Mr. Connolly said. “They’re going to screw up, and we’re going to pounce when they do. In their haste to remake the federal government, they’re going to make big, big mistakes.”

And the evidence of at least Trump ‘screw ups’ emerged rapidly. The particular initiative that generated a significant amount of chaos was the issuance of the freeze on government spending. In fact the freeze memo was quickly withdrawn though not before a federal judge on Tuesday temporarily blocked a pause on federal funding while the Trump administration declared it would conduct an across-the-board review. Even more chaotically the new press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, a quite blustery press secretary it seems I might add, insisted, however, that the spending freeze in the Order wasn’t being rescinded despite the memo that appeared to rescinded the freeze. Dan Drezner at his Substack, Drezner’s World, captured the craziness that has transpired recently with this flurry of executive orders, the freeze memo in particular:

Here’s the thing, though: to paraphrase Mario Cuomo, you can campaign seriously but you have to govern literally. And the first week of Trump 2.0 highlights the problems when an entire administration fails to make this particular pivot.

Needless to say, almost everything after “The American people elected Donald J. Trump to be President of the United States” is either factually or legally incorrect. Taken literally, it is a tsunami of bullshit.

Dan summed up this rather chaotic week for the Trump administration this way:

The White House and its co-partisans tried to backfill and claim that everyone overreacted and should have understood what the president really, truly meant. But that dog won’t hunt. As the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl — a pretty conservative dude — concluded, “the blame here lies entirely with the White House for releasing a terribly-written memo that did not include most of the guardrails they are now rushing to add as part of their next-day damage control. Perhaps the White House should try to get it right the first time.

If the Trump administration isn’t careful, they are going to blow their political inheritance and destroy the confidence of the American people. If they persist with “seriously but not literally” as a mode of governance, things will get real ugly real fast.

Now the chaos that broke out after the freeze memo kinda interfered with my effort to assess where Trump 2.0 was going with respect to US relations with China beginning with the Trump threat to impose 10 percent tariffs on China on account of fentanyl. Where is Trump 2.0 with respect to US-China relations? Well, interestingly Trump has not played up the US-China relationship yet, though the imposition of tariffs on China might well signal a change. And while Trump has threatened tariffs we need to see if, and or when they happen, and the bluster against China that will accompany the tariff announcement.

Meanwhile, Ryan Hass of Brookings has written a very interesting piece – “Can Trump seize the moment on China?” targeting the US-China relationship. He points to the very ‘heart’ of the competitiveness between the two leading powers:

This comprehensive approach [from China] to nurturing national economic competitiveness has generated eye-popping levels of industrial output. China is on pace to produce nearly 45% of global industrial output by 2030, according to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Outside of America’s industrial dominance in the wake of World War II, it is hard to find modern historical analogs to the levels of global concentration of output that are now occurring in China.

Ryan identifies from this massive industrial output advantage for China three risks. First there is the national security risk:

China’s factories and shipyards are on track to have production capacity for military equipment at a scale the United States and its partners could struggle to match. Already, according to Michael Beckley, China is embarking on the largest peacetime military buildup since World War II, producing ships, planes, and missiles five to six times as fast as the United States

Then, there is the risk to US social cohesion:

If America’s economy becomes too dramatically overweighted toward finance, technology, and services, it will leave a large portion of the population behind, resulting in a hollowed-out middle class and a yawning gap between winners and losers in the 21st-century American economy. Such a scenario would fracture the polity and create the seeds of social disorder.

Third, and relatedly, the overconcentration of industrial output in China would undermine America’s allies in Europe and Asia:

America’s long-term strategic interests would be ill-served if vehicle factories shutter across Europe and if Japan’s and South Korea’s industrial sectors are decimated by Chinese competitors. A core challenge for the Trump administration will be rebalancing global economic activity to ensure sustainable opportunities for growth in industrial output outside China.

Rebalancing is the key. But there also is the rub. It is very hard to see how with the current leadership of China, namely Xi Jinping, such a rebalancing is possible. The difficulties are underscored in an article by Zongyuan Zoe Liu in FA. This is an article published back in August entitled: “China’s Real Economic Crisis: Why Beijing Won’t Give Up on a Failing Model”. Zongyuan Zoe is currently the Maurice R. Greenberg Fellow for China Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. In the piece he wrote:

Despite vehement denials by Beijing, Chinese industrial policy has for decades led to recurring cycles of overcapacity.

Partly, this stems from a long tradition of economic planning that has given enormous emphasis to industrial production and infrastructure development while virtually ignoring household consumption. This oversight does not stem from ignorance or miscalculation; rather, it reflects the Chinese Communist Party’s long-standing economic vision.

As the party sees it, consumption is an individualistic distraction that threatens to divert resources away from China’s core economic strength: its industrial base.” According to party orthodoxy, China’s economic advantage derives from its low consumption and high savings rates, which generate capital that the state-controlled banking system can funnel into industrial enterprises.

And he then concludes:

For the West, China’s overcapacity problem presents a long-term challenge that can’t be solved simply by erecting new trade barriers. For one thing, even if the United States and Europe were able to significantly limit the amount of Chinese goods reaching Western markets, it would not unravel the structural inefficiencies that have accumulated in China over decades of privileging industrial investment and production goals.

Overlay this industrial focus by China with an intense competitive urges by members of the Trump team, starting with Marco Rubio, if not Donald Trump himself. Here is Rubio in his confirmation opening remarks speaking about China:

We welcomed the Chinese Communist Party into this global order. And they took advantage of all its benefits. But they ignored all its obligations and responsibilities. Instead, they have lied, cheated, hacked, and stolen their way to global superpower status, at our expense.

Hardly an attitude likely to generate serious considered negotiations between the US and China. And, then finally, add the necessary US approach to negotiations as seen and set out by Ryan Hass:

Trump’s team holds a variety of viewpoints on how to maximize America’s leverage, or even on what objectives America should pursue in its competition with China. Left unaddressed, this variance in views risks leading to policy incoherence. To overcome this risk, Trump will need to set a firm direction, identify specific objectives, and put his advisors on notice that they will pay a cost for actions that undermine his goals.

Look Trump’s transactional urges may surprise us all with movement on the US-China negotiating front but there is little, no, no way that Trump will undertake a more than reasonable approach as urged by Ryan. In fact Ryan describes what is likely to be the more telling direction and its consequences:

Absent firm and decisive policy direction from the top, there is a risk of policy chaos, with different factions canceling each other out and little progress being achieved to address American concerns about Chinese behavior. In such a circumstance, the U.S.-China relationship likely would grow more fractious. If Beijing abandons the hope of resolving U.S.-China differences through diplomacy, it likely will double down on efforts to hedge risk, including by deepening its relationships with countries who share antagonisms against the United States.

Based on what we have seen to date, I think we should ‘hunker down’ and anticipate a ‘risk of policy chaos’. More to come.

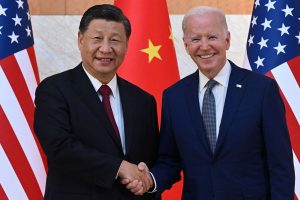

Image Credit: AP

I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship.

I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship. So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous

So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous