So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous Substack Post and particularly the Jessica Matthews’s targeting of Biden foreign policy in the upcoming Foreign Affairs article “What Was the Biden Doctrine? Leadership Without Hegemony”. As a reminder, this is what she wrote and I quoted in last week’s Substack:

So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous Substack Post and particularly the Jessica Matthews’s targeting of Biden foreign policy in the upcoming Foreign Affairs article “What Was the Biden Doctrine? Leadership Without Hegemony”. As a reminder, this is what she wrote and I quoted in last week’s Substack:

But he [Joe Biden] has carried out a crucial task: shifting the basis of American foreign policy from an unhealthy reliance on military intervention to the active pursuit of diplomacy backed by strength.

He has won back the trust of friends and allies, built and begun to institutionalize a deep American presence in Asia, restored the United States’ role in essential multilateral organizations and agreements, and ended the longest of the country’s “forever wars”—a step none of his three predecessors had the courage to take.

All of this happened in the face of grievous new threats from China and Russia, two great powers newly allied around the goal of ending American primacy. Biden’s response to the most pressing emergency of his term—Russia’s brutal full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022—has been both skillful and innovative, demonstrating a grasp of the traditional elements of statecraft along with a willingness to take a few unconventional steps. … But he has carried out a crucial task: shifting the basis of American foreign policy from an unhealthy reliance on military intervention to the active pursuit of diplomacy backed by strength.

Now I concluded that analysis with a Matthews’s quote with my concluding remark: “Now it seems to me there are questions over the effective use of diplomacy of this Administration but that is for another day.” Well this is another day and I want to focus a little on the current effectiveness of US diplomatic policy.

There appears to be a growing split over whether the US has had, or should I say, will choose to move forward with sharper diplomatic policies and initiatives rather than, if I can put it bluntly, ‘Reach for the Gun’. In fact, in the end, there are questions of whether the US will involve itself at all in serious but distant conflicts especially in the face of seriously weakened multilateral institutions. The foreign policy question is actually two questions then: will a Harris Administration respond to foreign policy crises with sharp diplomacy or resort to force and even more dramatically not only how the US may engage but whether it will engage at all.

Shortly after Harris and Waltz assumed the mantle of leadership of the Democratic Party that a strong positive view was identified. For instance Mark Hannah and Rachel Rizzo wrote the following in FP:

When applied to foreign policy, it could inform a pragmatic, forward-looking realism that’s all too rare in Washington. This sentiment aligns with a growing expert consensus.

A recent Carnegie Endowment for International Peace study concluded that the United States’ current approach to the world is “poorly adapted to the challenges of today and tomorrow.” It also noted a widespread demand among analysts for “a major strategic reorientation.” This reorientation could be from an everything-everywhere-all-at-once approach to a more judicious and strategic use of American might.

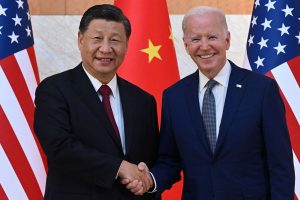

Let’s start with what appears to be the positive efforts of the current Biden policy efforts and conjure it as a likely course of action for a new Harris Administration. The immediate diplomatic approach is the recent Biden actions focused on its key geopolitical concern – that is its perceived strategic competitor and threat – its biggest rival – China. Notwithstanding the tough back and forth the two have undertaken recent discussions that appear to be designed to stabilize this most difficult bilateral relationship. The evidence for this is the recently concluded visit of National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan to China. This most recent meeting with Wang Yi who is the chief Chinese foreign affairs official for President Xi was not the first. For Sullivan and Wang this was one of a series of interactions as described by Demetri Sevastopulo in the FT:

It was the first of several secret rendezvous around the world, including Malta and Thailand, now called the “strategic channel”. Sullivan will arrive in Beijing on Tuesday [August 27th] for another round of talks with Wang in what will be his first visit to China as US national security adviser.

While the backchannel has not resolved the fundamental issues between the rival superpowers, says Rorry Daniels, a China expert at the Asia Society Policy Institute, it has aided each’s understanding of the other. “It’s been very successful in short-term stabilisation, communicating red lines and previewing actions that might be seen as damaging to the other side,” she says.

The two leading powers do not see ‘eye-to-eye’ on the role of diplomatic interactions. China in particular does not accept the framework of stabilization in the context of competition – the US view. Still, there does appear to be a certain diplomatic stabilization as described by Sevastopulo leading up to this most recent series of meetings in Beijing:

Sullivan strived to get Wang to understand the new reality — that the nations were in a competition but one that should not preclude co-operation. “That was a really hard jump for the Chinese,” says the second US official. “They wanted to define the relationship neatly [as] we’re either partners or we’re competitors.”

The Chinese official said China did not accept the argument. “Wang Yi explained very clearly that you cannot have co-operation, dialogue and communication . . . and at the same time undercut China’s interests.

They discussed possible deals for a summit, including a compromise that would involve the US lifting sanctions on a Chinese government forensic science institute in return for China cracking down on the export of chemicals used to make fentanyl. They also talked about resurrecting the military-to-military communication channels China had shut after Pelosi visited Taiwan. And they discussed creating an artificial intelligence dialogue.

Rush Doshi, a former NSC official who attended the meetings with Wang, says it was important to explain to China what the US was doing — and not doing. “Diplomacy is how you clear up misperception and avoid escalation and manage competition. It’s actually not at odds with competition but part of any sustainable competitive strategy.

And in this most recent set of meetings in Beijing, Sullivan was able to meet not just President Xi, important in and of itself, but critically a meeting with General Zhang Youxia:

Mr. Sullivan’s meeting with Gen. Zhang Youxia, vice chairman of China’s Central Military Commission, was the first in years between a senior American official and a vice chair of the commission, which oversees China’s armed forces and is chaired by Mr. Xi.

The Biden Administration regarded the Beijing meetings, therefore, as important diplomatic effort in stabilizing great power relations:

Sullivan tells the FT that he was under no illusions that the channel would convince China to change its policies, but he stressed that it had played an instrumental role in helping to shift the dynamic in US-China relations.

All you can do is take their policy, our policy, and then try to manage it so that we can take the actions we need to take and maintain stability in the relationship,” Sullivan says. “We have been able to accomplish both of those things.”

If managing great power relations was the US diplomatic goal, that seems to be successfully achieved for the moment. But that positive framing is not replicated in wider global order relations and the US efforts or lack thereof. Thus, the assessment of wider US diplomatic efforts is not nearly as upbeat. This is the message of Alexander Clarkson, a lecturer in European studies at King’s College London in his analysis of US foreign policy in his WPR article titled: “For Much of the World, the Post-American Order Is Already Here”:

This gradual waning of American influence outside of core areas of strategic focus rarely features in ferocious debates in Washington between those who believe that the U.S. should remain deeply involved in global affairs and the so-called Restrainers on the left and MAGA Republicans on the right who are skeptical of security commitments outside U.S. borders.

The limits of the United States’ ability to influence developments on the ground in destabilizing conflicts, or the responses of states engaged in them, have been particularly visible with civil wars in Myanmar and Sudan that barely feature in domestic American news cycles. In both cases, U.S. policymakers distracted by developments elsewhere failed to anticipate emerging escalation dynamics and then failed to develop the strategic leverage needed to rein in brutal armies and militias whose backing from other states rapidly widened devastating wars.

Washington’s flailing in the face of conflicts within Myanmar and Sudan that have now become wider geopolitical crises is a product of long-term shifts in the global balance of power. While Washington will continue to play a decisive role in managing conflicts that involve great power competition, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the tensions between Israel and Iran and China’s strategic assertiveness under Xi Jinping, in many other parts of the world the U.S. impact will be limited to diplomatic press releases expressing grave concern.

Clarkson sees US actions and inactions as a reshaping of the global balance of power. But I suspect it is an unwillingness to exercise direct diplomatic action to what is seen to be a distant conflict. It is also an evident result of the undermining, including by the United States, of effective diplomatic action by the UN. The weakening of the formal institutions – the WTO in trade policy and the UN in security and peace efforts – is now ‘coming home to roost’ at the US doorstep. US inaction is matched by the inability of these and other formal institutions to take on, stabilize and hopefully resolve difficult and potentially threatening conflicts.

The Harris Administration, if it wins, needs to address the manner of engagement but in too many instances the likely failure of foreign policy engagement at all. Much is currently wanting in US foreign policy. It is unclear if a Harris Administration is likely to tackle, and if so, how, these difficult foreign policy questions.

Image Credit: YouTube

This Post was originally posted at Alan’s Newsletter. Your comments are welcome as well as free subscriptions to Alan’s Newsletter

https://open.substack.com/pub/globalsummitryproject/p/us-tensions-over-a-leading-role?r=bj&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

It’s rather foolish to believe that even a ‘bullet wound’ would alter Donald Trump. His speech accepting the nomination for the Republican Party on Thursday night – over 90 minutes – proved that. What you see is what you get. But let me reflect for a moment on the consequences for Trump, and the political system, of this attempt on his life. Its impact it seems on American politics, and more particularly on the Trump third presidential run – well, at least for the moment, appears rather negligible. As Susan B. Glasser of

It’s rather foolish to believe that even a ‘bullet wound’ would alter Donald Trump. His speech accepting the nomination for the Republican Party on Thursday night – over 90 minutes – proved that. What you see is what you get. But let me reflect for a moment on the consequences for Trump, and the political system, of this attempt on his life. Its impact it seems on American politics, and more particularly on the Trump third presidential run – well, at least for the moment, appears rather negligible. As Susan B. Glasser of

The current state of the international system. That is what I hope RisingBRICSAM can tackle in the next set of posts. While I remain the named blogger here at RisingBRICSAM, I shall not be undertaking this task alone. Nope. I have been fortunate enough these past weeks to be working with a great set of recent, or near MGA graduates from the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto.

The current state of the international system. That is what I hope RisingBRICSAM can tackle in the next set of posts. While I remain the named blogger here at RisingBRICSAM, I shall not be undertaking this task alone. Nope. I have been fortunate enough these past weeks to be working with a great set of recent, or near MGA graduates from the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy, University of Toronto.