While you will see that the main focus of this Substack is on multilateralism, and its current failure, I couldn’t let Trump’s disrespect for the President of South Africa, Cyril Ramaphosa pass without some comment. Once again in the Oval Office, as described in the NYTimes, Trump let his lack of understanding, his lack of facts rule the day. It showed the absolute worst of Trump. The American people should be ashamed that a leader is willing to so distort US relations with potentially friendly leaders:

“In an astonishing confrontation in the Oval Office on Wednesday, President Trump lectured President Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa with false claims about a genocide against white Afrikaner farmers, even dimming the lights to show what he said was video evidence of their persecution.”

“The meeting had been expected to be tense, given that Mr. Trump has suspended all aid to the country and created an exception to his refugee ban for Afrikaners, fast-tracking their path to citizenship even as he keeps thousands of other people out.”

“But the meeting quickly became a stark demonstration of Mr. Trump’s belief that the world has aligned against white people, and that Black people and minorities have received preferential treatment. In the case of South Africa, that belief has ballooned into claims of genocide.”

One last point, a good point it appears, though still somewhat uncertain, Trump will attend, apparently, the G20 Summit gathering in November in South Africa. As reported in the NYTimes:

“South Africa presented a framework for a trade deal, the president said, and the two sides agreed to hold further discussions to iron out the specifics of an agreement. He said that Mr. Trump indicated that he would attend the Group of 20 summit in Johannesburg in November, despite suggestions by his administration that the United States might skip it.”

So now back to today’s main subject, multilateralism. Back in December 2024 in a Substack Post here at Alan’s Newsletter, “Focusing on the Future – Where are we on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and some other things?” I leaned on Homi Kharas, my good colleague at Brookings to give me some hope that states, many states, were turning to focus on the sustainable development goals (SDGs). And Homi and some of his colleagues did. As I wrote at the time:

“Even more pointedly, Homi suggested that a vein of optimism was called for. The reason: technology could provide the necessary fillip to efforts to achieve the SDGs. Under the header, “ Technology is finally delivering on its promise to make major economic production and consumption structures more sustainable””

While that may be the case for some it is clearly not the case for the second Trump administration. As Dashveenjit Kaurashveenjit Kaur wrote rather depressingly this last March in Sustainability News:

“The US has officially rejected the UN Sustainable Development Goals, citing sovereignty concerns and claiming a mandate from voters to prioritise American interests over global frameworks.”

“When world leaders gathered at the United Nations headquarters in New York in September 2015, they created what many called a “blueprint for a better future” – the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Then-president Obama pledged American commitment to the ambitious 15-year roadmap designed to transform our world by 2030.”

“This week, and the United States has executed a stunning, although not unexpected about-face: the Trump administration has declared it now “rejects and denounces” these very same global objectives, becoming what appears to be the first nation to abandon the framework since its unanimous adoption.”

“The consequential announcement arrived not through a high-profile press conference or presidential statement. Still, it nested in diplomatic remarks delivered by Edward Heartney, Minister Counselor to ECOSOC at the US Mission to the United Nations.”

““Put simply, globalist endeavours like Agenda 2030 and the SDGs lost at the ballot box,” Heartney stated in the prepared remarks. “Therefore, the United States rejects and denounces the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals, and it will no longer reaffirm them as a matter of course.””

Now maybe this declaration from a mid-level bureaucrat can ultimately be swept away if the Trump administration changes its mind – as we’ve seen it wouldn’t be the first occasion for sure, still the statement is rather chilling and appears to meaningfully undermine the multilateral effort that to this point not very successfully, notwithstanding two recent UN summits that focused wholly or in part on on the SDGs.

This episode is just a small part of the growing acknowledgement that the heart of multilateralism, the UN and its many specialized agencies are failing. Many of us concerned with global stability and order focus a fair amount on the numerous multilateral efforts. But there does seem to be a certain amount of denial going on.

Now, in this context of faltering multilateralism, I was attracted by the recent piece penned by my colleague, Peter Singer. Peter among other things writes the Substack Global Health Insights. Now Peter was special adviser to the director general of the World Health Organization from 2017 to 2023. He is today emeritus professor of medicine at the University of Toronto and a former chief executive of Grand Challenges Canada. Peter understands the faltering UN effort. As he posted recently at his Substack, in a piece titled, “UN leadership: relentlessly focused on results?”:

“Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has recently taken to tweeting, “The mission of the UN is more urgent than ever.” This is certainly true, but not in its current version — replete with process and plans. There is, of course, a reform initiative, called UN80; however, it seems more focused on managerial efficiency and restructuring than results. The UN needs a new mission: Get Stuff Done.”

With the current round of new leadership appointments, Peter turns to leadership, and its central importance:

“Yet despite their importance, the UN system has often struggled to deliver timely, measurable outcomes—an issue exacerbated by dwindling trust and funding. With Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) badly lagging and support for the UN increasingly under threat, the need for results-focused leadership [emphasis added] is more urgent than ever.”

“The UN desperately needs leaders who are singularly focused on delivering measurable results. Without results, there is no trust; without trust, there is no funding. Results must be the cornerstone of any leadership candidacy.”

If leadership is key, then, Peter points to critical upcoming opportunities for the UN system and what is necessary for the incoming leadership:

“A key lever is leadership. Over the next three years, (at least) three major UN bodies will select (or elect) new leaders: the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2025, the UN Secretariat in 2026, and the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2027. The future of the UN may well hinge on whether these new leaders possess one crucial characteristic: a relentless focus on results.”

“Results must be the cornerstone of any leadership candidacy.”

“This results focus is fully compatible with other perspectives that will drive these elections, such as gender and regional representation.”

“Having had experience with a UN agency election and tried (and not fully succeeded) to help transform a UN agency into one that prioritizes results above all, I witnessed firsthand the barriers that make implementing a results-focused strategy difficult.”

So as Peter portrays it what is necessary for successful multilateralism is leadership dedicated to results that can be shown. Only with this will trust be built and with trust, according to Peter, funding will be forthcoming. With that in hand, he then targets the current effort to choose new leadership:

“This is the acid test. Leaders who have a proven track record of achieving tangible outcomes are more likely to replicate that success at the UN. The UN is awash with process. But there is a gap between planning and execution.” …

“In addition to personal examples, candidates should be able to provide compelling analysis and tangible solutions for improving measurable results at the agency they wish to lead.” …

“From my experience, two elements are essential to fast-tracking progress: innovation and data.” …

“Effective governance is even more important than management. Leaders must work with governing bodies to improve the results focus of the organization. UN governance tends to focus more on planning and process than on execution and results.” …

“Changing the culture of an organization is key to making results-focused strategy, management, or governance sustainable. UN organizations tend to be highly hierarchical, which means leadership has an outsized impact on culture.” …

“As member states, civil society, and donors engage in these critical leadership selections, they must champion candidates who are relentlessly focused on results. The future of the UN depends on it.”

And with that Peter concludes:

“Nevertheless, imagine a UN system where, in five years, every agency is led by someone relentlessly focussed on results and on getting things done. It would be a very different—and far more effective and sustainable —UN than the one we see today.”

The ‘pitch’ for critical leadership is sensible and important especially in the context of upcoming leadership searches and appointments. But I remain hesitant to accept that this will ‘turn this ship around’. It seems to me that in the end the critical element remains national effort and the determination for members to forge collective policy whether health policy, climate change whatever. As Gordon La Forge. 2025 in his piece, “The U.N. Is Still the Best Forum to Tackle AI Governance”. Reminds us in his recent piece in WPR:

“The late Richard Holbrooke once quipped that blaming the U.N. for international dysfunction is like faulting Madison Square Garden when the Knicks lose. Put another way, the U.N. continues to struggle with what could be called the 193-body problem: Nation-states are the world’s dominant form of political organization, but they are neither well-equipped to solve planetary challenges nor designed to defend the best interests of humanity as a whole, which often conflict with national imperatives.”

It may require ‘coalitions of the willing’ to press ahead with new leadership on advancing critical and necessary policy. We cannot let the 193-body problem of the UN, or the ‘big boys’ problem, US, China and Russia to torpedo critical policy efforts. It is time to end just the talk. Using a plurilateral approach to push forward is critical though possibly incomplete. More on that soon.

Credit Image: UN Dispatch

This Post first appeared at Alan’s Newsletter: https://substack.com/home/post/p-164155148

All comments and subscriptions are welcome.

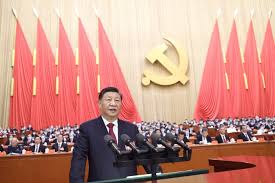

I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship.

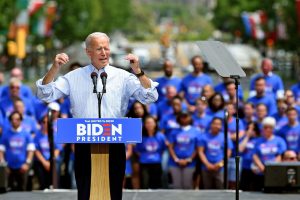

I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship. With just over 70 days until the US election, and with the certainty now of a new 47th President – either Harris or former President Trump – it is not surprising that analysts are scrambling to assess the current US foreign policy course and eyeing its new possible directions.

With just over 70 days until the US election, and with the certainty now of a new 47th President – either Harris or former President Trump – it is not surprising that analysts are scrambling to assess the current US foreign policy course and eyeing its new possible directions.