I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship.

I was intrigued by the recent efforts to understand and reveal the dynamic and direction of the US-China relations. In a global order where US-China tensions, or not, are likely the most consequential for either encouraging stability or instability in global affairs, new, and possibly some old insights, are key. It is why I was caught by a number of articles by colleague Ryan Hass of Brookings. Ryan is currently the Director of the John L. Thornton China Center and the Chen-Fu and Cecilia Yen Koo Chair in Taiwan Studies at Brookings. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for Asia Policy Studies and is, as well, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale Law School. Importantly, Ryan served as the director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia at the National Security Council (NSC) staff from from 2013 to 2017. In that role, he advised President Obama and senior White House officials on all aspects of U.S. policy toward China, Taiwan, and Mongolia, and coordinated the implementation of U.S. policy toward this region among U.S. government departments and agencies. The point of this Post: it is very helpful to follow Ryan’s recent assessments of the US-China relationship.

I found quite helpful a number of relatively recent articles by Ryan where he tries to understand what drives the US-China relationship. The current views range from: individual great power assessments of their own power in relation to their competitors; to a range of interactive actions between and among the great powers; to domestic drivers and their impact on relations with other great powers. I was pleased to see him assess various conceptions of great power actions and their impact on current global relations with a focus on US-China relations. So what drives US-China competition and explains in part stability in international affairs?

For Ryan it is the domestic factors that energize each country’s foreign policy actions as set out in his Brookings article from March titled, “How does national confidence inform US-China relations?”. As he writes in this piece:

Based on a review of the relationship over the past 75 years, this paper argues that when both countries feel secure and optimistic about their futures, the relationship generally functions most productively. When one country is confident in its national performance but the other is not, the relationship is capable of muddling through. And when both countries simultaneously feel pessimistic about their national condition, as is the case now, the relationship is most prone to sharp downturns. Domestic factors dictate the trajectory of relations. They do, however, play a larger role in influencing the relationship than otherwise has been observed in much recent public commentary.

This model for evaluating the relationship yields several policy-relevant conclusions. It suggests the relationship is dynamic and responsive to developments in both countries, as opposed to being captive to historical forces leading immutably toward conflict. It highlights that the relationship has navigated frequent zigs and zags over the past decades and rarely travels a straight line for long.” … The current task for policymakers in Washington and Beijing is to navigate through the concurrent down cycles in both countries while keeping bilateral tensions below the threshold of conflict.

Clearly, while the interactions of the two are important aspects of the bilateral competitive relations, it is domestic dynamics that are, according to Ryan, the significant drivers that promote cooperative relations or energize tensions:

At their core, both countries believe their governance and economic models are best equipped to meet the 21st century’s challenges. Both believe they are natural leaders in Asia and on the world stage. Both countries are contending with rapid societal transformations, which are being exacerbated by the impacts of the fourth industrial revolution. And both countries are determined to limit vulnerabilities to the other while seeking to gain an edge in emerging technologies.This is all occurring while the United States and China remain unsatisfyingly locked into a relationship that is at once both competitive and interdependent. The United States and China are competing to demonstrate which governance, economic, and social system can deliver the best results in the 21st century.

Thus in the present circumstances of US-China competition the following is the case, according to Ryan:

It [this article] argues that the United States and China presently find themselves in a simultaneous cycle of insecurity and dissatisfaction with their national conditions. Like when U.S.and PRC national down cycles have coincided in the past, this simultaneity is serving as a propellant in both countries for framing the national contest for power and influence in dramatic and, to some, existential terms.

Rather, by analyzing upturns and downturns in U.S.-China relations over the past 80 years, the U.S.-China relationship appears most prone to sharp volatility when both countries simultaneously are experiencing cycles of insecurity and pessimism about their futures.

That the U.S.-China rivalry has continued to intensify throughout the Trump and Biden administrations supports the argument that factors beyond the personalities and preferences of individual leaders inform the trajectory of U.S.-China relations. Trump and Biden are different in many respects. One through line of both of their presidencies, though, has been a sense of pessimism and loss of control among large portions of the American electorate about their country’s future.

Now the question is in the current political circumstance – with the end of Biden’s run for a second term and his replacement by Kamala Harris – what appears to be a far more optimistic leader, its seems to me, whether this may open up a stronger prospect that the US-China relations could, assuming a Harris electoral win, stabilize and open up the prospect for more collaborative global governance efforts led by the two leading powers?

Whether Ryan’s domestic framing is an adequate explanation for US-China relations is unclear. Ryan himself allows that this described approach is not a detailed empirical analysis of great power relations but rather more of a thought experiment.

Now it is clear that this approach, just described, is but one of many contenders for understanding the state of great power relations and more particularly the US-China great power relations. In particular Ryan raises some classic IR approaches. One in particular I was interested in and Ryan examines this which he describes as: “immutable historic forces or a function of their leaders’ personalities and preferences.” As he concludes:

In other words, the United States and China are not predestined to conflict based on past patterns between rising and established powers. The nature of bilateral relations also is not simply an extension of two leaders’ preferences and personalities. There are other factors involved, specifically both countries’ internal dynamics and their levels of confidence in their national directions.

So Ryan appears unenthusiastic over ‘simple’ great power dynamics that are urged by some IR specialists. He is not attracted to a view that focuses on the state of national power and a leader’s determination to act, or to not act, in the face of a leader’s assessment of immediate power advantage or not with rivals . Ryan mentions this in this Brookings piece but then tackles it more directly in a follow-on article where he describes in greater detail the framework, “peak power”. Ryan lays this out in an article titled, “Organizing American Policy Around “Peak China” is a Bad Bet” in China Leadership Monitor. The core argument in the ‘peak power’ thesis is that a great power, read that China, is more likely to act aggressively towards its competitors when leaders determine that that its national strength based on economic, political and military factors is waning:

China’s leaders explicitly reject suggestions that the country’s best daysare behind it. They believe China’s path to greater global influence is widening as America’s dominance in the international system wanes. It would be a mistake to organize American policy around “peak China” theory.

There certainly has been broad analysis that China, unlike in past decades, is currently struggling economically, demographically, and suffering push back from regional and other powers internationally and more. Chinese dominance regionally or even beyond is increasingly questioned. The peak power view of China has been popularized in part by two colleagues, Michael Beckley from Tufts and Hal Brands, the Henry A. Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at SAIS. Ryan examines their analysis of China’s leadership. As Beckly and Brands warned in a 2021 in a Foreign Affairs piece titled: “The End of China’s Rise,”the growing limits to China’s economic and political power. As Ryan suggests these IR specialists focus on strategic imperatives of great powers and their need to maintain influence and authority in the international system:

Such is the work of grand strategists who seem unconcerned about understanding China’s own vision and its strategies for securing it. Proponents of “peak China theory” treat the country as an inanimate object that is being blown off course by immutable historic forces. They assume that Beijing’s national ambitions resemble those of past rising powers that ran up against forces opposing their goals. Such analyses overlook the fact that China has agency. China’s leaders also maintain their own internal narratives and metrics for measuring progress in pursuit of their national objectives.

Ryan’s review leads him to this conclusion about China’s actions:

If any forecast of China acting as a peaking power is to hold explanatory value, there must be evidence that China’s leaders accept the diagnosis of their current condition and feel an urgency to act before their moment at the apex of national power passes. In the case of China today, no such evidence is available, at least not in the public record.

Now, I was encouraged by Ryan’s analysis of China’s power and actions to go back to the Beckley and Brands piece. Now to be fair, I should note that the two did produce a jointly authored book after the article and there may be a more elaborate explication in the volume of peak power and its influence on great power politics though most comments on their approach generally refer to the article. Here they describe what they see as the state of China’s international position in the face of declining domestic power factors:

China is a risen power, not a rising one: it has acquired formidable geopolitical capabilities, but its best days are behind it. That distinction China’s leaders are determined to move fast because they are running out of time. It matters, because China has staked out vaulting ambitions and now may not be able to achieve them without drastic action. The CCP aims to reclaim Taiwan, dominate the western Pacific, and spread its influence around the globe.

And from the article by Beckley and Brands there is surprisingly just this one paragraph in the piece that points to the consequences for great powers and the global order from the impact of peak power:

When authoritarian leaders worry that geopolitical decline will destroy their political legitimacy, desperation often follows. For example, Germany waged World War I to prevent its hegemonic aspirations from being crushed by a British-Russian-French entente; Japan started World War II in Asia to prevent the United States from choking off its empire.

Now I don’t want to extend this Post – it is already too long, and I have not read their follow-up 2022 study but I am underwhelmed by their explanation in Foreign Affairs. I have not examined closely enough the complex details of the politics of Japan before the war in the Pacific but I have examined closely the lead up to World WarI. Their view of Germany and its actions leading to World War I is just dramatically underwhelming. In my reading the crisis was driven by a decades-long decline of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and not just German aspirations and threat posed by Russia. And the state of the entente at the time of the July crisis was far from united, especially in looking at British views of the powers prior to the war.

But let’s not ‘get into the weeds’ on this. I am for the moment content to examine closely the analysis of China’s leadership by Ryan. It appears to reveal much about the state of US-China competition and geopolitical tensions in the current global order.

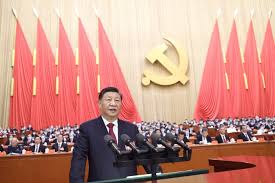

Image Credit: South China Morning Post