This past week ASEAN ministerial meetings popped up repeatedly in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh. These meetings served as diplomatic and political backdrop to the growing clash of interests in the seas east, west and south of China.

ASEAN has been a central player in Asian diplomatic and economic affairs since its formation in the late 1960s. But on its face this is not necessarily more than a important regional organization. Now, however, at least since 2008, one of the key ASEAN players, Indonesia, has also become a member of the G20 Leaders Summit. The ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) a security dialogue forum has reached out to include key players in Asia – most notably China and the United States. And the growing territorial claims especially, but not only, in the South China Sea have drawn in these key players to the security dialogue. Given that there is no larger security organizational setting where not just regional powers but also the great powers engage here, the ASEAN meetings do appear to fit into the global summitry galaxy of institutions.

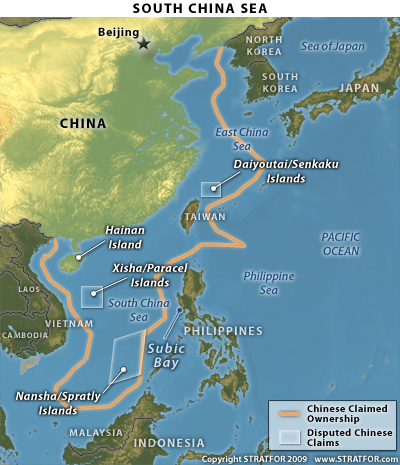

Much attention has been paid to the continuing tension that has hung over this region now for several years with contending territorial claims to the South China Sea by China, and various ASEAN and members including the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei and for good measure Taiwan. There have also been clashes between Japan and China over the East China Sea. The maritime area is a key for the global transport of goods and vital energy resources. Over half the world’s total trade transit through the area. And there have been increasing signs of resource riches – especially oil and gas – in the area as well.

The clash of interests was very much in evidence at, or surrounding the 45th ASEAN Foreign Ministers’ meeting in Phnom Penh early in the week followed by the ASEAN Regional Forum meeting. The ARF is one of the few diplomatic settings for security dialogue in Asia. This year’s ARF meeting – the 19th – includes not only ASEAN Foreign Ministers but dialogue countries including – Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, the People’s Republic of China, the European Union , India, Japan, North Korea, Republic of Korea, Mongolia, New Zealand, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Russia, East Timor, United States and Sri Lanka – 26 countries plus the EU in all.

Both meetings have highlighted the tensions between ASEAN and its allies and China. The United States has used these meetings to display rhetorical support for ASEAN countries without necessarily supporting any of the specific claims of these ASEAN countries. The US efforts would appear to be an effort since at least 2010 to insinuate itself in East and Southeast Asia – and draw closer to various ASEAN states especially Vietnam and the Philippines.

In the South China Sea the ASEAN FM have been pushing to engage China in a long standing effort to resolve conflicts between the various states. On Monday the FM sought to complete wording for a document to set out a Code of Conduct. The Philippines have pressed for wording that would include measures to resolve territorial disputes and to raise the conflict in the Scarborough Shoal between the Philippines and China.

Manila appears to be leading the ASEAN push to persuade China to accept a Code of Conduct (COC) that would go some way to resolve the territorial disputes themselves. There has been a ten-year effort to complete a code of conduct which most ASEAN leaders have see as a legally binding document that would govern the behavior in the various seas and “establish protocols for resolving future disputes peacefully”. (see the WSJ “Beijing Defends Sea Claims as Clinton Visits Region” by Patrick Barta July 11, 2012)

China has been unwilling to discuss such a document signalling instead that it would be prepared only to discuss a more limited code aimed at “building trust and deepening cooperation” but not one that settles the territorial disputes, which it insist would be better negotiated with each country separately. In the current diplomatic settings China has urged that officials leave discussions off the agenda.

For China, the collective ASEAN effort to promote a binding COC has posed unwelcome interference in what Beijing has described not as territorial disputes between China and ASEAN but only disputes with some ASEAN states. China has insisted that resolution of these conflicts be undertaken bilaterally.

Since the 2010 ARF meeting the United States Secretary of State has made it clear that the United States supports a multilateral solution and insists on the freedom of the seas:

Issues such as freedom of navigation and lawful exploitation of maritime resources often involve a wide region, and approaching them strictly bilaterally could be a recipe for confusion and even confrontation.

The Chinese position has remained adamant in the run-up to the ARF that US and various ASEAN positions were “deliberate hype” and intended to interfere with relations between China and ASEAN. The Foreign Ministry continued to insist that the issue be left off the ARF agenda.

Meanwhile in the East China Sea tension rose significantly after two Chinese patrol vessels entered waters claimed by Japan. This incident followed an announcement that the Japanese government was considering buying the Senkaku Islands (referred to by the Chinese as the Diaoyu Islands). Though the announcement was part of a complicated negotiation by the current Noda government caused by strong domestic political interests, the announcement and tensions quickly engaged both Japan and China.

A full blown diplomatic row at the ARF was only avoided when the ASEAN countries failed to reach agreement on the language of the COC. But the tensions and potential conflict remain.

China has certainly not backed away from the its diplomatic positions. And as the most recent East China Sea incident with Japan suggest is prepared to exert measured “military” action to underpin its assertion of interests. Meanwhile has expressed a view that inserts itself into the regional conflict – and likely garners ASEAN country support – but at a low immediate cost while not directly challenging China – yet.

For the moment US-China engagement retains the “upper hand”. But the position could well sour were military action – even though likely of a rather limited sort and unlikely to be between the US and China – were to occur.

Miscalculations and mistakes happen.

Image Credit: Stratfor 2009