So returning to Steve Clemons’s and his review of grand strategy approaches in the Atlantic with his “Rebuilding America’s Stock of Power” which itself is a lead in for Steve to lead an Atlantic Live session that will be streamed live on January 11th. Well, I hope to get there but meanwhile let me attempt a partial review of Steve and his review of various ‘in the beltway’ types in the most recent issue (Issue 23, Winter 2012) of Democracy: A Journal of Ideas.

Steve has an outsized personality that is a Washington and New York presence. Now Steve is a realist – a ‘happy realist’ – but a realist nevertheless. The ‘bug-a-boo’ for Steve is the rise of China. As Steve points to:

China is driving realities in the global economic sphere today; not the United States – and America, to revive its economy, needs to figure out how to drive Chinese-held dollars (along with German and Arab state held reserves) into productive capacity inside the United States while not giving away everything.

America must knock back Chinese predatory behaviors by becoming more shrewdly predatory and defensive of America’s core economic capacities. Without a shift in America’s economic stewardship – which also means a shift in the macro-focused, neoliberal oriented, market fundamentalist staff of the current Obama team – the US economy will flounder and on a relative basis, sink compared to the rise of the rest.

For these experts, and for Steve I suspect, it is all about finding restraint in a new US grand strategy. With the end of the Iraq War for the US and a growing intensity to end their military involvement in Afghanistan, there is a loud and growing chorus of voices in Washington to husband US resources. Turn down the urge to go abroad to slay dragons. The attack is on against unrestrained US interventionism which Steve argues is, as he calls it, “the dominant personality” of both US political parties. So for the Democrats you have the humanitarian interventionists – read that as Libya – and for the Republicans you have the neoconservatives’ regime change – read that as Iraq. The critique from Steve:

Neoconservatives and liberal interventionists put a premium on morality, on reacting and moving in the world along lines determined by an emotional and sentimental commitment to the basic human rights of other citizens – with little regard to the stock of means and resources the US has to achieve the great moral ends they seek.

So restraint and husbanding resources – economic and military – is the new objective. And each of the experts, in their own way, urge it. Thus Charlie Kupchan declares that in order to rebuild American leadership the US must:

- restore the American consensus on foreign policy and the rebuilding of its economy;

- work with the newly emerging market powers to create a new global order and protect a liberal international order;

- revitalize the transatlantic relationship; and then

- judiciously retrench and deal with the overextension of US global commitments.

In a similar vein a quick look at this recent press release at the CFR website for Richard Betts’s new book entitled, American Force: Dangers, Delusions, and Dilemmas in National Security, Betts too recommends, “the United States exercise greater caution and restraint, using force less frequently (“stay out”) but more decisively (“all-in”)”.

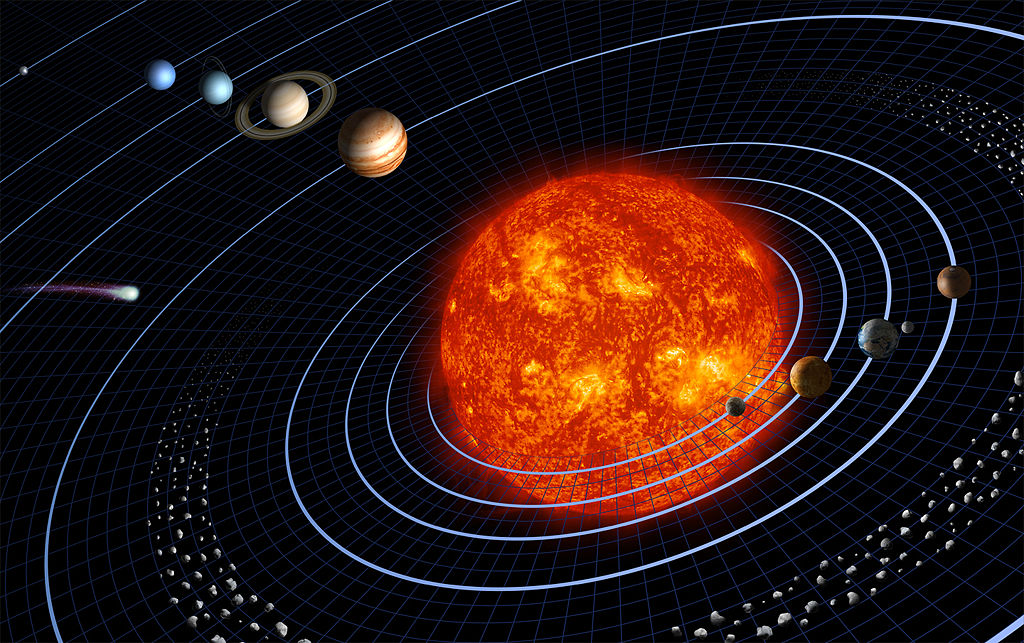

Bruce Jentleson performs a reprise of his and Steve Weber’s approach in The End of Arrogance. In the journal article Bruce narrates a Ptolemaic versus Copernican world, where the central image is the displacement of the US from the center of the universe. Now contrary to more realist interpretations, this diffusion of power as described by Bruce, anticipates that China too – the new rising power – will be unable to exert hegemonic power in this new 21st century global system. As Jentleson declares,”Peaceful rise is one thing, assertive dominance quite another.” The Copernican world, according to Jentleson, is a disorderly place, but a global order that, “… means demonstrating the capacity to implement policies that reduce our vulnerabilities, enhance our competitiveness, and cultivate a shared sense of purpose.”

Diffusion of power, the end of hegemony or at least the enlargement of leadership with the inclusion of the rising powers like Brazil, India and China, and a requirement that the United States husband its resources – economic and military.

Steve argues that he holds a line similar to the Kupchan approach though he criticizes Kupchan for holding to such neatly drawn pillars of action for the US. But it seems to me that constraint has been the mantra of the US before – back to the 1970’s and the end of Vietnam. It is not a strategy and it is apt to be forgotten, or ignored, by a new political leadership especially across the political divide that exists in the US. The dilemma that exists today is not a search to enunciate some new grand strategy, but an effort, and here I tend to agree with Bruce Jentleson, to ‘lead’ in initiating collective behavior – the impetus for collective action. And there needs to be a concerted to avoid the China Threat syndrome that is embedded in Washington. Restraint will evaporate unless US policy makers find a way to open a political space for China. This is the overwhelming need in US foreign policy. In the coming years, according to the review of Richard Betts’s book

China is the main potential problem because it poses a choice Americans are reluctant to face. Washington can strive to control the strategic equation in Asia, or it can reduce the odds of conflict with China. But it will be a historically unusual achievement if it manages to do both,” notes Betts. Although conflict with China is not inevitable, “the United States is more likely to go to war with China than with any other major power.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons