I could not resist – and a big thanks to Joni Mitchell and Judy Collins for the reference to their famous tune. I f you recognize the reference – well you know …

In 2009 I think – the draft of this book chapter was done in 2008 – Zhang Yunling of CASS – “Mr. APEC” in China – and myself wrote a chapter on the regional dimension in the US-China relationship in an edited volume by Gu Guoliang and Richard Rosecrance called Power and Restraint: A Shared Vision for the US-China Relationship. Zhang Yunling and I tried to capture the US-China relationship this way at the time:

China’s strategy is based on three principles: first, China recognizes the United States as a superpower; indeed the current sole superpower; second , China will cooperate with the United States in as many areas as possible; and third it would seem China will continue to increase its strength, including military strength, and raise its status both regionally and globally. From China’s perspective, as long as the United States recognizes and takes into account China’s interests, China is unlikely to challenge the overall US leadership. In the final analysis, the most significant question for China is, how can it balance its support for democracy, domestically and externally, with the defense of sovereignty whether Taiwan, Central Asia or the Asia-Pacific generally?

Well, that was then and this is now! It would not appear to me that these constitute the bedrock “rules” that define this most important bilateral relationship. But let’s take a look at the rules and where the relationship is today.

The context has changed a great deal since the full onset of the global financial crisis of 2008. It appears that the “Chinese foreign policy elite” – I am not sure exactly who these people are – but there is a view from western experts – I know these folks far better – that there is a from Beijing the view that the US is in decline and that it is losing its hegemonic status. Furthermore, and more ominously, as a result in part of the US Administration’s “Asian pivot”, these same China experts have a heightened suspicion that the US is unwilling to adjust to its relative decline and China’s rise. As Brooking’s Kenneth Lieberthal recently described it at ForeignPolicy.com:

In Chinese eyes, the United States has always been concerned primarily with protecting its own global dominance – which perforce means doing everything it can to retard or disrupt China’s rise. That America lost its stride in the global financial crisis and the weak recovery since then while China in 2010 became the world’s second-largest economy has only increased Beijing’s concerns about Washington’s determination postpone the day when China inevitably surpasses the United States to become the world’s most powerful country.

So it would seem that China has drawn back from the view that the US is the only superpower. Instead many China experts now suggest that China is a global power as presumably is the United States. Quite honestly I haven’t s clue what a “global power” is – and I suspect it is simply a way for Chinese experts to assert that China is a superpower – without having to actually proclaim it. There is little question that both states are great powers – lord knows no one would question each being in the G20 etc., but then including India also makes sense. Clearly India is not yet a “global power”. It seems to me to be disingenuous to manufacture this new category – especially if you compare the two by military or economic metrics – it ain’t so. I think too many experts distort time lines. It more than a decade, possibly two, before China’s economy will match the US so let’s not conflate that future with the present. And as for the military and strategic partnerships – not even close.

Though it is true that the US and China have sought to cooperate in a number of critical areas – especially in the global economy, notably China’s leaders urging collective effort to resolve the eurozone crisis and to avoid grater turbulence – in other areas there is no collaborative spirit. Most puzzling is China’s determination to support Russia to the bitter end on Syria. It is unnecessary and with little that would suggest that there is a Chinese interest in playing “poodle to Putin”.

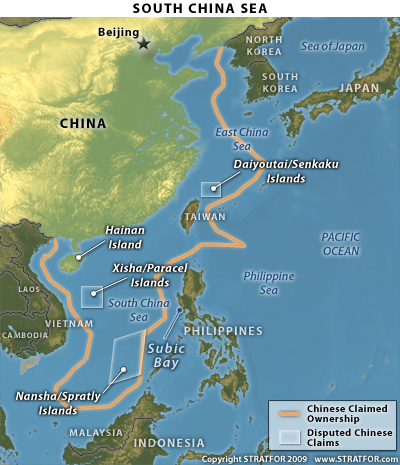

More contentious are the growing demands and “police” encounters in the South China Sea between China a number of Asian countries. China has asserted a broad territorial claim that encompasses much of the South China Sea. In addition there are territorial clashes between China and the Japan in the East China Sea. Many in Washington have declared a new China assertiveness threatening regional stability. The US has meanwhile – without declaring sides on the territorial claims, has insisted on freedom of navigation and a multilateral approach to resolving the territorial demands. China has in turn rejected this approach – and at least for now has insisted that these territorial claims should be settled by the contending parties only – bilaterally in other words.

The new assertiveness has enabled many in Washington to focus on the growing military modernization in China’s armed services and calls to meet such military challenges. The point here is that the so-called new assertiveness has drawn close attention to China’s military threats and the consequences of the growing military modernization.

Where then do the two great powers need to go? Here are some actions that the two can adopt that are likely to lower the temperature on the competition, lead to a new set of rules and can be accomplished largely without the other:

- Both take a deep breath and limit the degree of hedging each proposes for the other. Hedging focuses on worst case and frequently results in outcomes each is concerned to hedge against;

- The US de-emphasize rhetorically the Asian pivot; work more quietly with ASEAN allies to generate a Code of Conduct acceptable to both sides;

- China turn down the volume on the South and East China Seas and at least in the case of the South China Seas propose concretely joint development agreements with the parties – Vietnam, Philippines, and others. These agreements enable the parties to side step the territorial claims for the present; and

- China needs to rethink its Syria position in the UN and consider abstention as opposed to veto.

I was fortunate enough early in the week to hear former Australian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister speak on the Rise of China. If you take a look at the NewStatesman.com the article entitled “The West Isn’t Ready for the Rise of China”, the piece fairly reflects his remarks at the Munk School of Global Affairs. I thought I’d just provide a quick sense of the approach that Rudd brings to this critical relationship:

So, what then is to be done? Is it possible for the west (and, for that matter, the rest) to embrace a central organizing principle as we engage China over the future of the international order? I believe it is. But it will require collective intellectual effort, diplomatic co-ordination, sustained political will and most critically, continued, open and candid engagement with the Chinese political elite. So, what might the core elements of such an engagement look lie?

I will turn to Rudd’s perspective. This should allow me to describe the new rules of collaboration required for the US-China relationship.

For this particular “thought exercise”, I will try and describe what are the rules of behavior that can ensure that the competitiveness and rivalry can be contained – that rivalry and competition do not escalate to heightened and sustained rivalry – and then even to conflict.

Image Credit: abc.net.au