Final reflections on the Harvard-Beida conference on US-China relations (see previous blog posts for further information). If I was a meteorologist, I would suggest that the weather forecast for US-China relations has gone from, partly sunny to partly cloudy.

A number of international relations experts examining the Asian architecture recently have described a growing polarity in the structure of pan Asian relations. So, for instance Evan Feigenbaum now at the Paulson Institute (a former US official) and Robert Manning (also a former official) but now at the Atlantic Council described in “A Tale of Two Asias” in October in foreignpolicy.com that Asia today consisted first of a “Security Asia” described by the two as “a dysfunctional region of mistrustful powers, prone to nationalism and irredentism, escalating their territorial disputes over tiny rocks and shoals, and arming for conflict.” And there was a second Asia, what the two authors called “Economic Asia”, a dynamic, integrated Asia with 53 percent of its trade now being conducted within the region itself, …”

The first pole, according to Feigenbaum and Manning is dominated by the United States while the second has become increasingly dependent on China. For the two experts the dilemma posed by this structure is that Economic Asia is increasingly seen to be at risk by the rise of nationalism and the growing security competition in the region. As Feigenbaum and Manning have written recently in the East Asia Forum in a piece entitled, “The Problem with the Two Asias,” a response to a critical piece written by American University’s Amitav Acharya’s “Why Two Asias May be Better Than None” also posted at the East Asia Forum:

Our principal point is that Asia’s incredible economic dynamism and growing integration are at risk because of debilitating security competition and sharpening political disputes within the region, not just between the United States and China, but among Asia’s major economies as well. … Put simply, competing nationalisms and the scars of national memory remain potent forces in Asia. And they risk undermining the economic gains that have done so much too promote integration, boost growth and foster opportunity.

At our own conference at Beida, our colleague John Ikenberry from Princeton sketched a similar two pole pan-Asian architecture. Acknowledging a division in the structural construction between security and economics in Asia, Ikenberry proposed that the longstanding partial US hegemonic order, as he called it, is giving way to:

In effect, as noted earlier, there increasingly are two quasi-hierarchies in East Asia. There is an economic hierarchy led by China and a security hierarchy led by the United States. This circumstance creates constraints and dilemmas for the United States.

Now most suggest that the reassertion of classic balance of power dynamics in Asia would be detrimental to all and lead to growing friction and rivalry between the US and China and put pressure on the powers in Asia to choose one or the other. Ikenberry puts well the unease that appears to pervade Washington circles today:

At the same time, the United States does see China today in the way it has seen potential regional hegemonic rivals in the past. It is worried that China could amass sufficient wealth and military power to fundamentally alter East Asia. The ultimate danger is the growth of a Chinese rival that would endeavor to drive the United States out of the region and project illiberal ideas and policies outward into the world.

I think the “two poles” construction today still distorts the current Asian architecture. Feigenbaum and Manning point to the fact that 53 percent of Asia’s trade is now conducted in an intra-regional basis identifying this datum, and others, as indicating that “Asian economies have become increasingly reliant on pan-Asian regional trade.” But a quick comparison with other regions shows the strength of intra-Asia’s broad intra-regional trade but suggests that it is hardly excessive. EU intra-regional trade as a percent of global export merchandise trade is 26 percent as opposed to Asia where the intra-regional trade is 16 percent. Furthermore, any examination of global value chains would suggest that in fact long valuable chains stretch to Europe and North America. And EU-Asia trade as a percentage of world trade comes in at 3.6 percent. This rather too static look at intra-Asia trade and the growing China trade presence in Asia, I believe does lead falsely to a conclusion that there is a security pole, headed by the US, matched by an economic pole dominated by China.

That being said there certainly does appear to be rising nationalist sentiment in Asia among the key players. And there is no question that interdependence is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for stability in the global environment – though I would suggest that “complex interdependence” – globalization, generates a quality different than say the interdependence in the period before World War I.

So what conclusions can one derive from our conversations at Beida and in the surrounding informed blogosphere debate? Here is a part of what I take away from the conversations and readings:

- China is ‘driving the bus’ in the region in many issues – especially on the island/islets dispute – and it is driving it in the wrong direction. China repeatedly appeals to acting only in response – a reactive stance – in the South and the East China Seas island disputes. But for many, “one man’s reactive is too frequently aggressive behavior to the other”. The apparent manipulation of the Cambodia host at the most recent ASEAN gathering and the continuing unwillingness to contemplate seriously a binding Code of Conduct or to put the sovereignty disputes away for cooperation on resource development, are all unhelpful and raise the temperature over these disputes. As Joe Nye so aptly described, “only China can contain China” so as China has become more assertive China, in fact, has begun to contain China in the region (see a more developed view by Nye following the conference posted at the NYT). So China responding

with more measured cooperation here would be a fabulous starting point for the new China leadership if it was determined to lower the temperature;

- China experts need to consider abandoning a view that every action by the US has only China in mind and that all US actions are designed to contain China. The US, in fact, has been a primary supporter of Chinese leadership building its economic strength and achieving greater prosperity for all Chinese;

- Much attention was paid to the overreaching of the “Pivot” both in US actions but most especially in its rhetoric. A number of US experts were critical of what they saw as the unnecessarily aggressive statements of US officials. One expert urged that US and China focus on solutions that preserve face for both suggesting a start with much broader exchange and cultural programs. Another arguing the reduction in assurances by the US to China urged that the US undertake efforts to build trust. He has urged in the past that the US could give way on the close-in surveillance of the Mainland, made unnecessary by other surveillance means.

- The US, according to many at the Conference needs to work very hard to avoid “balance of power” actions. Instead, a look at Stephen Walt’s proposals seem designed in particular avoid balance of power actions. Walt urges (see his blog post at foreignpolicy.com) positive and negative security cooperation including the involvement of the US and China. On the positive side he points to possible cooperation on Iran, Korea or anti-terrorism. It does strike me that Korea is a most apt choice, especially given the DPRK’s recent threats against the US. On the negative forms of cooperation surely greater efforts to conclude a multilateral Code of Conduct led by the US and China and useful for both sets of island disputes could be extremely valuable.

There is likely more. Let let me conclude here nevertheless. The cloudy forecast is a result of the insidious impact of rising nationalism in China, Japan, Korea and elsewhere. It is time for the new China leadership and the renewed US leadership to build trust and lower the nationalist temperature throughout the Asia-Pacific region.

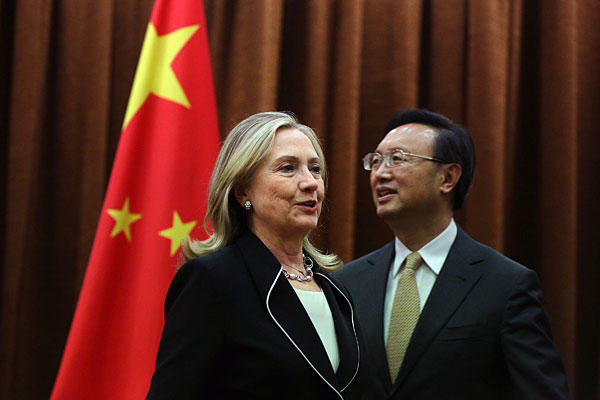

Image Credit: www.bbc.co.uk