Time flies in China – the exception being travel by car anywhere in China – indeed anywhere in Asia pretty much.

Time flies in China – the exception being travel by car anywhere in China – indeed anywhere in Asia pretty much.

In any case time to leave Dalu and return to Canada. But meanwhile I’ve had meetings with colleagues from the academy and think tanks in Beijing and here in Shanghai and most importantly I joined the Shanghai Conference hosted here by the Shanghai Institutes of International Studies (SIIS) in partnership with the Stanley Foundation (TSF) and my own Munk School of Global Affairs.

This just past Conference was not the first. Indeed a year ago we worked to bring together experts from all the G20 Asian countries to examine the prospects for collaboration among the G20 Asian countries. This year we worked to bring together experts from the Asian G20 countries plus now the Pacific G20 countries – the United States, Canada and Mexico. Mexico’s presence in particular was valuable as Mexico will host the G20 Leaders Summit in June 2012.

This Shanghai meeting was telling. One, we had historical memory. David Shorr our colleague from TSF was quick to note that there appeared to be maturation in the thinking of experts. A year ago experts from the region were grappling with the emergence of the G20 Leaders Summit. Was this new informal leaders summit legitimate – representative? What was the place of this summit as opposed to the G8 or the UN or the many regional organizations? These legitimacy questions were largely absent from this most recent gathering. Instead there was a serious examination of the transition of the Summit from crisis gathering to permanent summit. There was serious evaluation of the success in meting the key policy objectives, global financial reform, SSBG – Strong Sustainable and Balanced Growth, or macroeconomic imbalances in the global economy, and several other economic reforms including development and food security and food price volatility.

What were some of the bottom line conclusions? Though these several phrases hardly captures the full discussion and assessment they do help reflect G20 Summit evaluation. First there was a strong sense among experts that the G20 risked serious underperformance. There was a near consensus that experts feared little in the way of ‘deliverables’ or even ‘announceables’. I must admit that I added to that view. I argued that the G20 currently suffered from a major ‘case of distraction’ both for the French Presidency but also for European G8 members. The distraction was evident – the European sovereign debt crisis. This sense of distraction needs some clarification. The continuing crisis in the Eurozone occupied growing attention for France and indeed all of Europe. While contagion in the global economy was a real threat from possible disorderly Greek default and continuing and indeed growing volatility in financial markets, my assertion was that the crisis still represented a distraction for the G20. The key source of resolution lay with the primary European actors – France and Germany. There lack of willingness to take critical decisions and calls for support by the IMF and the G20 kept drawing G20 attention to a serious crisis that principally needed to be addressed by Germany, France and the European Central Bank.

The attention to the sovereign debt crisis seemed to have drained energy from the macroeconomic imbalances focus of the G20. Now our colleague Dan Drezner who joined us from the Fletcher School – and who has been highly critical – of the results of G20 coordination efforts – concluded that the macroeconomic coordination efforts were ‘Mission Impossible’. Past macroeconomic coordination efforts had largely come ‘a cropper’ and in some cases had made matters worse than better. But still he urged that the G20 should in fact do more if not necessarily in the global imbalances policy arena. Later he even quietly admitted that he was impressed with the Mutual Assistance Process (MAP) efforts but still unclear about the outcomes of the coordinated policy effort.

When examining the coordination efforts of Asian G20 countries, experts still noted the dramatically limited collaboration among the G20 countries in Asia. But the fear of blocs had diminished from a year earlier and our colleague Lee Dong-hwi from IFANS in Korea urged Asian G20 countries to step up their collaboration. As he put it, Asian countries could usefully increase ‘caucusing but without caucuses.’ In the face of global imbalances and in the light of economic circumstances here in Asia, there was growing support for caucusing without fear of generating blocs.

The Conference realized that there was a growing fear that without deliverables and in the face of the continuing global economic crisis, the G20 needed to show progress or risk being labeled irrelevant. While many experts looked to move the G20 Leaders Summit to a more crisis prevention stance that the leaders had to balance with the need to show policy progress in a growing crisis atmosphere. Such balancing was difficult but unavoidable.

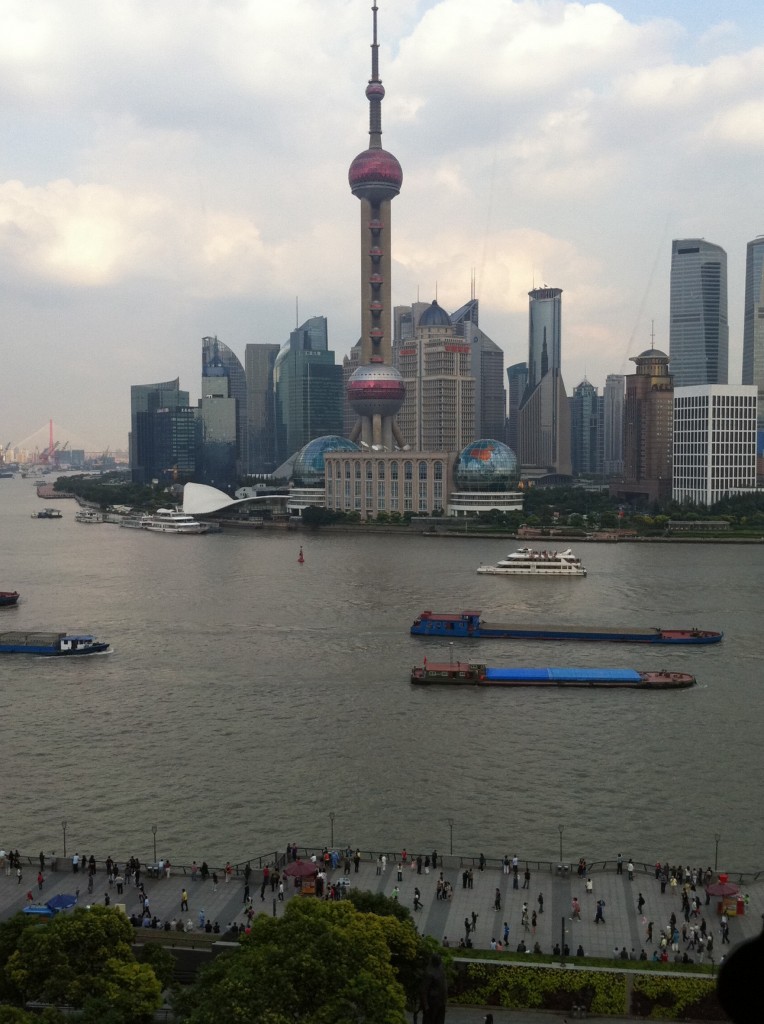

Image Credit: copyright Alan S Alexandroff