Experts are trying to puzzle through exactly what Chairman Xi Jinping has in store for US-China relations now that the power transfer has been completed in China and Xi has been named President. There appear to contending views from the US side on the future of the US-China relationship. There is one school – attractive for the “China Threat” and grand strategy types – that focus on Xi’s reference to “The China Dream”. For some others, myself included, less ‘exercised’ by the China Dream possibilities and intrigued – but aware of the empty content so far in Xi’s proposal – a reference to “a new type of major or great power relationship”. It is worth exploring both to try and tease out Xi’s think, if we can.

The China Dream 中国 之梦 -zhong guo zhi meng

Many of the China Threat types have raised concern over Xi Jinping’s reference to the ‘China Dream’. Though it is officially described as the ‘rejuvenation of the nation’, the focus for most is President Xi’s series of talks to the military on the ‘China Dream’.

This title, as has been described by a number of sources, also reflects a book that was written some 3 years ago by Colonel Liu Mingfu of the PLA and a professor at National Defense University. As described by Jeremy Page, a Beijing reporter for the WSJ in a recent article entitled “For Xi, a ‘China Dream’ of Military Power”, the book by Liu Mingfu predicted a “marathon contest for global domination”. Though suppressed soon after the publication – it was viewed apparently, as likely to cause damage to US-China relations – a new edition was approved just shortly after President Xi gave the China Dream speech. And in the run up to the final leadership transition Xi Jinping has made it a point to speak to various groups of the military. Chairman Xi, for instance, told a group of sailors late last year aboard a guided-missile destroyer that had patrolled in the hotly disputed South China Sea that “To achieve the great revival of the China nation, we must ensure there is a unison between a prosperous country and strong military.”

All this has led many in US diplomatic, strategic beltway and analyst circles to believe, according to Jeremy Page that:

… Mr. Xi is casting himself as a strong military leaders at home and embracing a more hawkish worldview long outlined by the generals who think the US is in decline and China will become the dominant military power in Asia by midcentury”.

So those attracted to this view and Xi’s efforts to woo the military see:

… Mr. Xi is setting the stage for a prolonged period of tension between China and neighbors, as well as for a potentially dangerous tussle for influence with a US that is intent on reasserting its role as the dominant Pacific power.

In setting out apparently on this more military and aggressive policy, Xi appears to be setting aside the doctrine expressed by Deng Xiaoping: 韬光养晦 (taoguang yanghui) – concealing one’s capabilities; biding one’s time; to have an achievement. Many have identified the more assertive behavior of the former leadership since about 2010 – in the South China Sea and more recently in the East China Sea, as a product of greater national aspiration and great power determination. According to Xinhua news, President Xi expressed the following to the Politburo

… but we will absolutely not abandon our legitimate rights and interests and absolutely cannot sacrifice core national interests.

The closeness to the military and the reflections on a more aggressive approach has led President Xi to issue orders to focus on “real combat” and “fighting and winning wars.” It certainly appears an evident contrast to the previous leadership of Hu Jintao who seemed to keep a very low military profile. But President Xi may well have adopted various territorial and nationalist perspectives that were seen to be confined before to largely military hawks to secure strong military loyalty. Why, is still unclear. It may be to secure the loyalty of the military as Xi prepares, perhaps. for serious economic reform. We really don’t know, though there is much speculation. Time will tell.

But then on reflection while the policy shift may be now, military capabilities are quite another. What China can bring to this “party” are not anywhere near what the US currently possesses and deploys in the Asia-Pacific. And the China Dream at least as expressed by Liu Mingfu is decades away. And the desire to build the military resources of the Chinese military – aircraft carriers and stealth fighter jets – are costly weapons systems that may yet prove to be yesterdays war tools. As today’s platforms become increasingly vulnerable, serious military spending on today’s costly weapons systems may prove to be a serious and not very effective weapons path. And I always look at the official weapons expenditures and double the amount. Why? Well at least in the recent past China – state and party – have spent about as much on internal security as they have spent on the military. This is not a Party operating from strength, but perhaps, fatal weakness.

In the final analysis the China Dream is founded on US decline. Today the military gap between China and the US remains demonstrably large (for 2013 China is proposing – at least officially – a budget of $119 billion while the US budget calls for $553 billion) . The key player in this relationship is surely the United States – as much as it is China. While there are voices that seek the US to lower its profile in the international system or that the US can shift to some notion of offshore balancing to get others to do what is necessary, reduce defense costs and maintain US influence, the reality appears to be that the US is moving in the opposite direction in the Asia-Pacific. And while the Defense Department will be required to participate in the ‘right-sizing’ of the US budget, including weapons procurement, US decline does not appear to be evident – or on the horizon. There is however, one policy change that could alter the strategic equation and nudge US-China relations toward a “New Type of Great Power Relationship”.

新型大国 关系 – (Xin xing daguo guanxi) – new type of great power relationship

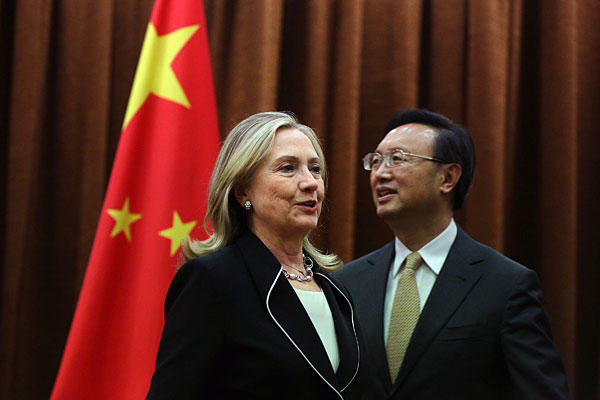

So alert to the potential turn in relations, yet not entranced by the China Dream perspectives, what then of a new type of great power relationship. As I mentioned earlier there is nothing at the moment that fills this particular diplomatic and strategic vessel. But in reflecting back on the conversations that a number of colleagues and I had in January in Beijing at the Harvard-Beida conference I came away with one overwhelming conclusion – China experts – possibly not officials but maybe – believe that the Obama pivot is a policy targeting China and indeed a strategy all about China and US determination to contain China and remain the hegemon in the region and beyond. Moreover the China experts suggest that the US pivot will give comfort to Vietnam, the Philippines and most especially Japan to advance more aggressive stances with China in the continuing “Island Disputes.” Especially with the latter, US diplomacy can be effective in alerting allies quietly, especially Japan that the US has little appetite for crisis and no appetite for conflict, intended or not. The same needs to be conveyed quietly to China. Publicly the US needs to avoid some of the more pointed language that former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton publicly prone to express, though she claimed to be advancing a neutral stance. This even-handedness is obviously most difficult with the Japanese, where security guarantees tilt US statements. Overall the US needs to frame the Pivot in a wider frame of diplomatic and economic engagement – and away from a military focus.

So a tuning of US policy toward greater diplomatic and economic policy in the Asia-Pacific is the bedrock for a new type of great power relationship. In addition while greater competitiveness is evident in the US-China relationship, there are possibilities of collaboration. In a recent assessment of the US-China relationship at the China US Focus David Shambaugh, from George Washington University, and long time observer of China and the US-China relationship acknowledges the deep interdependence of the two in what he sees as a ” … predominantly competitive relationship with a major power with which it is simultaneously deeply interdependent.” He characterizes the need for a new relationship as:

For all these reasons, President Xi Jinping and the new Chinese leadership is wise to put forward the desire for a “new type of major power relationship.” It is definitely needed – because the “old type” of competitive and suspicious relations is now predominant in the bilateral relationship. … While establishing such a “new type of major power relations” is a desirable aspiration, this observer believes that “managing competition” is the more feasible reality. To establish a relationship of “competitive coexistence” is more realistic.

It would appear that David has bowed – at least a little – to a more contemporary framing of the US-China relationship – it is primarily competitive. It leans in the direction of the characterizations expressed by the IR China scholar Yuan Xuetong, the Director of the Institute if International Studies at Tsinghua University, accepting the current enmity and rejecting superficial friendship, extending the meaning of the traditional Chinese perspective – (非敌 非友) (fei di fei you) – “neither friend nor foe”.

亦敌 亦友- (yi di, yi you) – both friend and foe

The traditional expression it seems to me to leans too far in the direction of a competitive relationship. The slight turn of the traditional phrase, above, which I have commented on in earlier blog posts appears to me to better situate the two – highly interdependent powers in a periodically competitive relationship. So unlike earlier competitive power transitions, this relationship is defined as much by high economic interdependence and various potential global or near global collaborative leadership settings, e.g. APEC, EAS and the G20. This doesn’t suggest that the road map to a new type of great power relationship is self evident or inevitable but it does set off this competitive relationship from the host of earlier power transitions – whether US-Soviet or Germany and Great Britain before World War I.

It leaves me to suggest that there are a number policy steps that the US – and for sure China can take – that can help build a new type of great power relationship:

- As noted above the US needs to widen its “Pivot” and underscore that it is as much diplomatic and economic as it is political and security. And I would think that the advice from Harvard’s Stephen Walt at the Harvard-Beida Conference, and then on his return to the blogosphere, warrants policy exploration. He urged policy efforts of both positive and negative cooperation. On the positive side the evident possibility is the DPRK and there has been some sanction cooperation between the two. There needs to be more and that requires – I suspect President Xi – to press the PLA to bring greater reality to the DPRK military;

- President Xi also needs to take note of Harvard’s Joe Nye’s realistic strategic framing – only China can contain China – and that its “assertive behavior” has accomplished exactly that in the region;

- President Xi can take a giant leap – and I suspect this is more in the realm of wishful thinking – and put to the test the US position that the TPP (Trans Pacific Partnership) is not designed as an anti-China economic initiative, by signalling its interest in joining the talks now that Japan appears to have signaled the same; and

- Then in the realm of perception and policy followup both the Chinese and US leadership and the cognoscenti circling the leadership need to avoid framing the relationship in “Cold War” terms. It is all too comfortable for policy makers and the military to see the relationship in growing competitive even growing rivalrous terms. Perceiving it may in fact hasten it. Now that is really a bad idea!

Image Credit: topnews.in