G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bankers have wrapped up their meeting in Mexico.

So what’s the result?

Well the battle has not yet been won to create a significant enough “firewall” to calm the markets and assure them that contagion will not spread beyond Europe.

But it appears to be coming.

The heart of the issue is Germany’s reluctance to add to the bailout fund that had been created – Europe had first built a temporary fund – the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) and then subsequently created a permanent European Stability Mechanism (ESM). That combination would total about 750 billion euros. But Germany is not yet ready to do that. And the G20 – or at least many of the G20 countries – are not prepared to augment the IMF support standing around $358 billion by some $500 to $600 billion – until Europe makes a greater contribution.

The G20 countries have pressed Europe (see the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bankers Communique) – that means principally Germany in this case – to increase the European contribution. It is still unclear whether Germany is prepared to commit – it would appear not to be by next week at the European Summit set for March 1 – 2nd.

Where do the G20 countries stand – and why? Most critical in this discussion is Germany. And Germany has resisted – and continues to resist though apparently less vociferously the enlargement of the Eurozone’s bailout fund.

Germany appears, in part, to be playing for time. The German Government faces a crucial vote in its legislature on Monday – a vote to accept a second rescue package. – As a bit of an aside the Netherlands and Finland also face legislative approval in the coming week. It also seems that the German government is playing for time to see if the Greek government will be successful in swapping Greek debt held by banks and other investors that propose a significant reduction in the face value of the debt, or drawn out maturity and/or rate reductions – or all three. And the Merkel government is all too aware that German public opinion is strongly opposed to to further bailout actions for Greece. In fact in a poll released today, Sunday, by Bild am Sonntag (quoted in Reuters) showed that 62 percent of Germans oppose further aid for Greece. Thus, the German government for the moment continues to insist that an enlarged firewall may cause governments to ease up on their fiscal austerity measures and additional economic reform. The strongest views from the German government continues to argue that the ESM is sufficient as it is. In the meantime, however, Greece, Ireland and Portugal are locked out of debt markets.

Most of the G20 countries – developed and large emerging markets alike – have urged Europe to take further steps to reduce the risk of contagion. A number of developed countries such as the UK and Japan are prepared to raise further IMF support along with a number of developing and large emerging market countries, most insist that will not act without further actions by Europe. And the United States has both urged greater European actions but has also made clear that it will not contribute in any instance to the enlargement of the IMF package.

So it is unclear today whether Europe will enlarge the bailout at the March EU Summit or that a complete package – somewhere near $2 trillion including European and IMF funds – will be ready or concluded by the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bankers when they meet again toward the end of April. But we can see that the G20 Ministers and Central Bankers meeting has been important in trying to construct a bailout package. Furthermore in looking at the comments of the ministers and central bankers there is not a simple divide between developed and large emerging market states and developing countries.

Speculation over the legitimacy of the G20 continues apace. But the legitimacy focus is ill placed (see the Reuters blog – “The Great Debate” and the article by Terra Lawson-Remer, february 24, 2012) . The current troubles in constructing a bailout package reflect popular and legislative opposition in a number of countries – Germany most notably – but in other European countries as well and in the United States. This is not a G20 legitimacy debate at all; it is a political battle in the domestic and international contexts. That fact that executives and their officials cannot act without calculating legislative dis/approval is not new – remember the “failure” of the Kennedy Round in the US Congress. But this says next to nothing about G20 legitimacy. What it reflects is that global economic negotiating, indeed almost any international negotiating – as we were told long ago by Harvard’s Robert Putnam – requires officials to negotiate in two ways – across the table with other leaders and officials, and backwards and over their shoulders with the legislators and broader publics of the country. The “high table” of international economic negotiations has never been leaders and officials divorced from domestic politics. And it isn’t now.

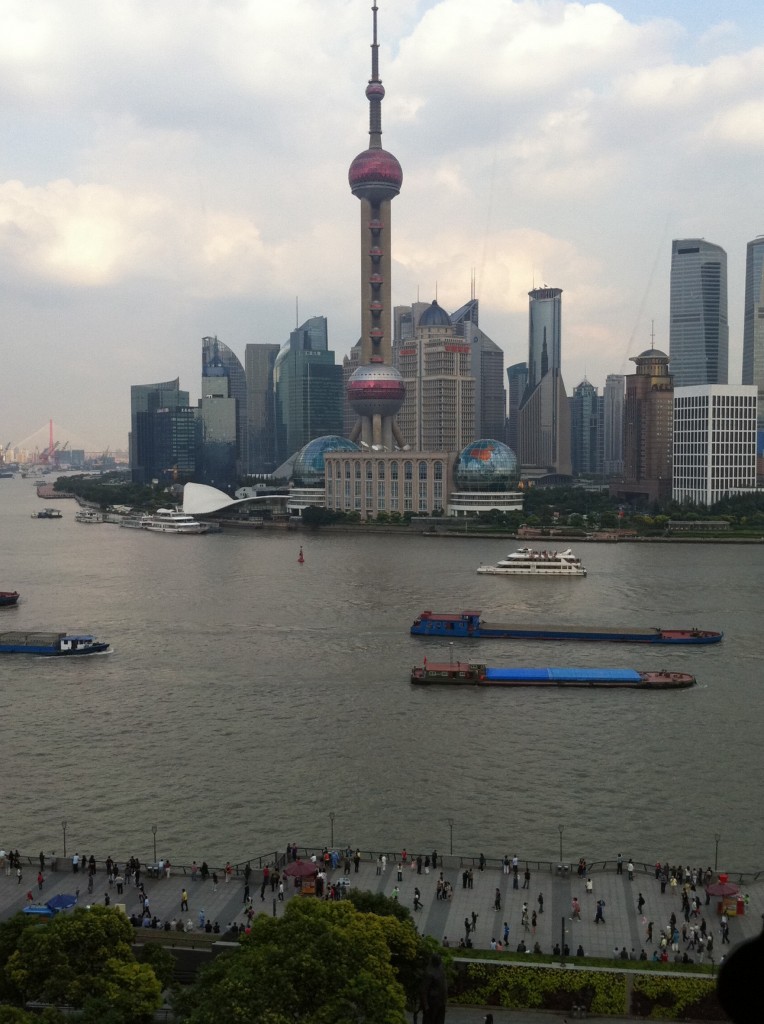

Image Credit: Chris Skinner – Financial Services Club Blog