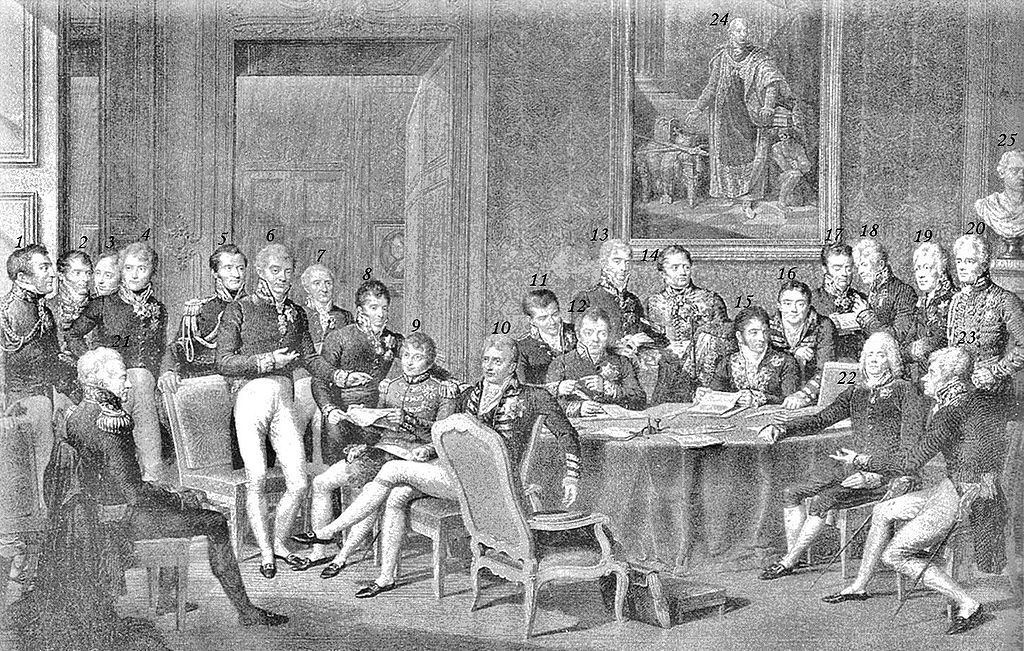

Great power rivalry has forcefully reappeared. It is a jolt for anyone that follows international governance to watch the Russian actions in the Crimea and to hear the assertions and rationalizations by Russia’s President Putin concerning Russian annexation of the Crimea.

Category Archives: Global Summitry

A World in Flux

I was going over Richard Rosecrance’s explication on UCTV of his his latest international relations thesis: The Resurgence of the West: How a Transatlantic Union Can Prevent War and Restore the United States and Europe. His analysis demands comment. But not right at this moment.

‘Good Enough Global Governance’ Maybe – But is It Really Such a Global Muddle?

So my colleague and friend Stewart Patrick, the Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program at the Council on Foreign Relations has given us a full picture of the contemporary global governance system recently in Foreign Affairs.

So my colleague and friend Stewart Patrick, the Director of the International Institutions and Global Governance Program at the Council on Foreign Relations has given us a full picture of the contemporary global governance system recently in Foreign Affairs.

But say it ain’t so Stewart. The bottom line for him is an unruly and largely unorganized global governance architecture delivering only partially what is needed:

The future will see not the renovation or the construction of a glistening new international architecture but rather the continued spread of an unattractive but adaptable multilateral sprawl that delivers a partial measure of international cooperation through a welter of informal arrangements and piecemeal approaches.

And Then There was a New Host – Australia

Quietly, maybe a touch too quietly, Australia assumed the hosting duties of the G20 on December 1, 2014. As one of the first initiatives under Australia’s presidency, the program director of the G20 Studies Centre at Australia’s Lowy Institute, Mike Callaghan convened a Think20 session in Sydney. So as in Russia, and before that in Mexico, representatives from G20 think tanks and G20-focused academic centers gathered in the mercifully warm and sunny city of Sydney.

Growth in The Middle: Arriving on the Scene – MIKTA

So forget the BRICS, or even IBSA. The newest grouping is MIKTA. MIKTA stands for Mexico, Indonesia, Korea, Turkey and Australia. All these countries are members of the G20. It would seem that the group met at the margins of the UN General Assembly opening.

The Stars Appear to Not Be Aligned – The G20 Summit in St. Petersburg

So putting the last items in the bag for the trip to St. Petersburg. This one looks like trouble. Five years in to G20 Leaders Summits and St. Petersburg would appear to have all the characteristics of a major distraction. This would not be the first. I certainly remember how the Greek Euro crisis drove France’s G20 Agenda at Cannes right off the cliff. It would appear that Syria – and the use of military force in retaliation for the use of chemical weapons – could be even more of an agenda killer.

Without Trust and Without Paranoia: US-China Relations

It was a time for informal face-to-face contact – just ended – the California summit between Presidents Xi and Obama. There is a strand of global summitry that emphasizes contact between leaders. Such contact can be disastrous of course. Kennedy’s encounter with Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961, left leaders with misconceptions about the other that ultimately led each to take steps that raised threats and crisis. Let’s hope that nothing like this occurs as a result of this summit. And the reality is that the ‘world of summits’ has changed mightily. The two presidents will see each other again shortly in St. Petersburg Russia at the G20 Leaders Summit. And they will meet again shortly thereafter in Asia at the EAS.

It was a time for informal face-to-face contact – just ended – the California summit between Presidents Xi and Obama. There is a strand of global summitry that emphasizes contact between leaders. Such contact can be disastrous of course. Kennedy’s encounter with Khrushchev in Vienna in June 1961, left leaders with misconceptions about the other that ultimately led each to take steps that raised threats and crisis. Let’s hope that nothing like this occurs as a result of this summit. And the reality is that the ‘world of summits’ has changed mightily. The two presidents will see each other again shortly in St. Petersburg Russia at the G20 Leaders Summit. And they will meet again shortly thereafter in Asia at the EAS.

What can we draw as the consequences of this informal meeting of the leaders of these two great powers? Ostensibly the two leaders are searching for a “new type of great power relationship” (xinxing daguo guanxi) – The announcement of this informal summit and the search for a different kind of relationship – read all that as an effort by IR types to avoid what international relations theory tells is the likely outcome of rivalry, friction and conflict between an established superpower and a rising one. Thus many of the foreign policy experts have indeed waded in to describe what might result from such a meeting – and give some expression to the ongoing Sino-American relationship.

Stephen Walt at Foreign Policy, the consummate realist suggested a modest result:

Neither Obama nor Xi can alter the core interests of the two countries, or wish away the various issues where those interests already conflict or are likely to do so in the future. The best they can achieve is a better understanding of each other’s red lines and resolve and some agreements on those issues where national interests overlap. In this way, each can hope to keep things from getting worse and at the margin make relations a bit warmer. … But even if Obama is successful this weekend, this effort is unlikely to prevent Sino-American rivalry from intensifying in the future. The basic problem is that the two state’s core grand strategies are at odds and good rapport between these two particular leaders won’t prevent those tensions from reemerging down the road.

Walt acknowledges the description just referred to is a pessimistic one (he does describe a far more optimistic alternative) based on “… Sino-American rivalry in the future no matter how well Obama and Xi (or their successors) get on this weekend. And so for Walt “intense competition is likely”.

Then there is Walt’s FP compatriot – Dan Drezner. Now Drezner is no realist – and in fact in some ways leans more to a neo-liberal framing of international relations (I suspect Dan may not buy this). But Drezner reflected on this upcoming summit at his blog (I anticipate that this blog post is not his final word on this) by referencing Harvard’s Iain Johnston in a piece Jognston wrote recently for International Security examining the growing Chinese assertiveness – which Johnston largely rejects. The lesson for Drezner is China is no revisionist power. As he argues, “Since 2008, China has had multiple opportunities to disrupt the US-Created international order, and Beijing has passed on almost all these opportunities.” So for Drezner the landscape is filled with collaborative opportunities between the US and China:

Now let’s be clear – China is doing almost all of this to advance its own narrow self-interest. None of the above means that China is suddenly going to embrace the US perspective on human rights or the South China Sea. Still, there are a healthy number of issue areas where China’s interests are pretty congruent with the United States, and where China has taken constructive policy steps. … My main point here is that China is a great power that is inevitably going to disagree with the United Sattes on a host of issues. China is not, however, a revisionist actor hell-bent on subverting the post-1945/post 1989 global governance. To use John Ikenberry’s language, recent Sino-American disputes are taking place within the context of the current international order. They are not about radical changes to that international order. Indeed, contrary to the arguments of some, the current system has displayed surprising resilience.

In a curious way this perspective resonates if only a little with a far more pessimistic view – that expressed most pointedly by Yan Xuetong the Dean of the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua University. A strong nationalist, and realist, Yan Xuetong is not well known outside China-expert circles. FP did themselves and their publics a great favor in printing a post by the Dean entitled, “Let’s Not be Friends“. For some time now Yan Xuetong has been arguing that leaders and their officials should not promote a vision of a trust-based collaborative relationship – those arguing for it will only be disappointed. The US and China are competitors. But that need not prevent incidents of collaboration:

States cooperate not because of mutual trust, but because of shared interests that make cooperation safe and productive. China and the United States should look hard to identify what these incentives and shared interests are – and focus on developing positive cooperation when their interests overlap or complement one another, such as on denuclearization of the Korea Peninsula, and preventive cooperation when their interests conflict, such as on preventing collisions in [the] South China Sea. … Preventive cooperation differs from positive cooperation because it is based on conflicting — rather than shared — interests. … Areas of friction are likely to become more common in the coming years, but the two countries can skillfully manage their competition if they work to minimize these emerging conflicts — not only in the military sector but also in nontraditional security sectors such as energy, finance counterterrorism in the Middle East, anti-piracy in Somali Sea, and even climate change. … Encouraging China and the United States to prioritize preventive cooperation does not mean they should abandon efforts to build mutual trust. However, it does mean the two countries can stabilize their strategic relations without it. The worst-case scenario is not that China and the United States is not that China and the United States will face more strategic conflicts in the coming years, but that they never learn how to develop cooperation based on the lack of mutual trust, thus allowing a small conflict to escalate into a major one.

I suppose it is a framing a little like: “don’t trust but verify”. The dilemma I fear however is that all this realist formulation will lead – at least in US circles if not Chinese ones – to analogize the relationship to something like the cold war contestants, even as they draw distinctions between the two sets of rivals. Simplistic competitive framing is too easy and too familiar. The Washington-types that always lean on “hedging” and insist on greater military preparedness will target the competitive and forget the collaborative. Inexorably the US and China will be characterized as the new cold war rivals.

I have argued for the necessity of wedging cooperation into the relationship and rejecting any logic to US-Soviet competition. In the past I have argued that “both friend and foe” (yi di yi you) is the better framing for the great power relationship than “neither friend nor foe” (fei di fei you) – a framing often used by Chinese experts. Starting at the post, “Not Required to Choose – A Strategy for US-China Relations” I have argued that defining the relationship as including a collaborative dimension is necessary to avoid sliding into a more difficult unpleasant great power relationship. Yes, it will be difficult especially for US decision-makers to retain the partnership aspect – that is both collaborative and competitive. -Without that collaborative element to the relationship, however, Washington leadership will be all too willing to accept just a rivalrous competitive relationship with China. It is after all politically so much easier.

Let’s not make it easy for the claque.

Image Credit: channelnewsasia.com

Caucuses, Counterweights or Leadership – The Evolution of the G20

A quick trip to London enabled me to enjoy the valuable discussion at a small gathering brought together at Chatham House. The conference sponsored by Chatham House and the Australian Lowy Institute spent the good part of a day examining “From the G8 to the G20 and Beyond: Setting a Course for Economic Global Governance.” Presentations by officials, former officials and policy experts produced a rich context for informal discussion.

My own view was that the most intriguing discussion of the day was a back and forth over the evolving summitry structure. Now I know there will be an immediate chorus of sighs – oh geez architecture again – but the summitry structure has important implications for the global economy and the conduct and stability of international relations. So back to the discussion.

I think there was a general consensus in the room that the large emerging market powers – frequently labelled as the BRICS countries – were failing to take up leadership at the G20. This view was aptly described recently by Harvard’s Dani Rodrik. In a piece first posted at his blog and then slightly enlarged upon at Project Syndicate – my favorite economics blog site – Rodrik examined the recent efforts of the BRICS, most notably at the BRICS Leaders Summit at Durban.

Rodrik in these posts took the opportunity to first express disappointment in what is at the moment the signature initiative of the BRICS – the effort to launch a development bank, which Rodrik described rather disparagingly in the following terms:

This approach [infrastructure financing] represents a 1950’s view of economic development, which has long been superseded by a more variegated perspective that recognizes a multiplicity of constraints – …

But Rodrik did not stop there. In a criticism that was reflected in various comments at the conference, Rodrik argued:

What the world needs from the BRICS is not another development bank, but greater leadership on today’s great global issues. … If the international community fails to confront its most serious challenges … they are the ones that will pay the highest price. Yet these countries have so far played a rather unimaginative and timid role, in international forums such as the G-20 or the World Trade Organization. When they have asserted themselves, it has been largely in pursuit of narrow national interests. Do they really have nothing new to offer?

One of the conference participants took direct aim at this tepid leadership. He suggested that the premature death predicted for the G7 and now arguably countered by revival and renewed energy evidenced by the G8 or more precisely the G7, might conceivably pressure the large emerging market countries to step up to take greater leadership in the G20. It might indeed be true that the G7 efforts especially on economic questions might give the BRICS the kind of fillip that might cause them to step up in the G20. But equally possibly these countries, the BRICS especially, might view the G7 activism as isolating the BRICS – not to mention the non-G7, non-BRICS countries like Australia, Korea or Turkey – and give impetus to those who see the BRICS as a conscious counterweight to G7 and its economic statements.

Certainly circumstances conspired to show the economic efforts of the G7. For the day following the conference the G7 finance ministers and central bankers met outside London at Aylesbury. In a statement by the UK Chancellor George Osborne the Chancellor targeted the vital economic questions of the day, “monetary activism, fiscal responsibility and structural reforms.” There certainly wasn’t consensus on these difficult issues but you coud see the rising image of the established powers working on these key economic issues as they have for decades before the emergence of the G20.

It would be a terrible waste, not to mention a destabilizing step were the G20 to lose momentum and to fail to serve as the common setting for the established and rising economic powers. Certainly the meeting of these groups at the margins of various G20 meetings can be seen to be helpful – indeed they already have – but the focus on separate coalitions is overall in my estimation unhealthy for global summitry. The G7 needs to be sensitive, more sensitive then they appear to be currently, over their gatherings and the absence of colleagues from the rest of the G20.

Let’s not throw away the first and best setting for collaborative efforts between established and rising states. Both form and substance are required.

Image Credit: G7 Finance Ministers May 11, 2013 Alyesbury – google.com

The ‘Hare and the Tortoise’ – Global Media and their Continuing Harsh Assessment of the G20

Now I think it was my colleague Dan Drezner over at Foreign Policy who spent some time – at the moment I am at a loss to remember the exact piece – defending the G20 against the dismissive attacks that members of the media are so fond of producing following a G20 meeting.

Well our friends – in this case Chris Giles and Robin Harding at FT – were hard at it at the G20 finance ministers’ and central bank governors’ meeting during the just recently concluded ‘Spring Meetings’.

Here is a gem of a comment from these two media souls:

Since 2010, it has turned from being a cohesive group of te world’s most important economies, ensuring they took collective decisions to solve difficult problems, into a body that spends hours negotiating the punctuation in a communiqué that adds little. … Countries still value the G20 greatly as a forum for dialogue, but complain that too many nations sit round the table and make unnecessary interventions, with little genuine discussion. It has turned into a talking shop without much bureaucracy or idea of its role. Outside a crisis, when nations want to solve problems and are willing to make sacrifices, the G20s relevance to people and companies is diminishing rapidly.

Mean spirited at least. But are the two right? Their judgment seems to me to ignore again, the “incremental” but necessary efforts of contemporary global summitry decision-making. The contrasting views expressed are bit like a “hare and tortoise” assessment of the G20. Media looks for the success of the hare and is continually disappointed; for some of us this is about the tortoise and we remain patient.

Look it would be great to have this grand bargain-style G20 – the kind these two media folk and other media types seem to crave but that is not what the G20 offers – nor indeed do many other global summitry settings. These summits are iterative and depend on the hard work of working groups, ministerial gatherings, sherpa meetings, secretariat work and the work of developed transgovernmental regulatory networks. The constant reference by media and experts to the actions of the G20 at the abyss in 2008 and 2009 hardly defines the manner in which the G20 acts. The current efforts on financial reform and SSBG – strong sustainable and balanced growth – are difficult policy developments. So a quick look at the boring communiqué is required. Some takeaways:

- advanced economies will develop medium-term fiscal strategies by the St. Petersburg G20;

- setting a global standard for public debt management – the IMF and the World Bank will consult with members on implementation and review of “Guidelines for Public Debt Management.” A progress report will be made to the Leaders Summit;

- The possibility of providing additional policy recommendations to the Leaders Summit on regional financing arrangements (RFAs) and strengthening cooperation between the IMF and RFAs;

- The efforts to mobilize long-term financing that includes adoption of the Terms of Reference of the new new G20 Study Group with input from the IFIs, OECD, FSB UN and UNCTAD with possible recommendations for the finance ministers and central bank governors later in the year;

- assessments from the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (BCBS) on the compatibility of Basel III and the BCBS regulations including a report in July on risk-weighted assets;

- the FSB will report to the Leaders Summit on the efforts to identify the policies on how resolve financial institutions in an orderly manner – the “too big to fail” issue;

- FSB concluding the legislative and regulatory reforms for OTC derivatives reforms;

- The FSB providing to finance ministers and central bank governors the macroeconomic impact study of OTC regulatory reforms;

- Policy recommendations for the Leaders Summit on oversight and regulation of the shadow banking sector;

- A call from the finance ministers and central bank governors to the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) US to conclude by 2013 the work of achieving a single set of high-quality accounting standards;

- Recommendations from the Bank of International Settlements (BIS) and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) on short-term interest rate benchmarks with recommendations for reform by July and in turn oversight and governance frameworks for financial benchmark reform to be presented to the Leaders Summit;

- the launching by the FSB of a peer review of national authorities’ steps to reduce reliance on credit rating agencies’ ratings – with a status report to be provided to the Leaders Summit;

- a report from the OECD on progress toward countries signing or expressing interest in signing the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters and a report back from the OECD -following work with the G20 – on new multilateral standard on automatic exchange of information; and

- a July report from the OECD with comprehensive proposals to the finance ministers and central bank governors on tax base erosion and profit shifting.

Worthy of headlines from the media – probably not. To the extent that these actions and reports don’t lead to key national commitments – meaning regulations and laws – then our media friends may be right. But progress in some or all of these many initiatives warrant some attention. And it is all this work that media folk are quick to just ignore.

I would also say that collective discussion – contentious though it may be – over Japan’s quantitative easing policies – is important. For the moment, it would appear that most of the G20 are prepared to accept that these Japanese actions are not steps in competitive devaluation, which might, if so described, lead to national responses that could harm many. We will have to see, however, the impacts on some of the large emerging market countries and then their responses.

Finally, on the economic growth front it is evident that the G20 believes that not enough is being done to counter global economic weakness. Clearly a key culprit in this is the EU and in particular the eurozone, though the UK figures in as well. This of course appears to be a continuing drama from the close to irresponsible actions in the eurozone. I have consistently argued that the G20 has little role here – but to urge a change of course which it appears now to be doing. But the G20 is constantly being dragged into this European drama.

The bottom line is that the media misses the work in progress – and announces failure. I think that is going too far at this point.

Image Credits: logo – www.pnswb.org and picture – www.nannewsngr.com

Rising to a Summit – Australia’s Kevin Rudd and US-China Leaders

Kevin Rudd, the former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Australia has been on the “speechifying path” recently – I guess that’s what comes with others running the show. He has been in North America and in the granddaddy of foreign policy journals – Foreign Affairs – he has provided an interesting addition to the examination of US-China relations – “Beyond the Pivot: A New Road Map for US-Chinese Relations“. But my suggestion is that rather than a road map his piece is more detour as he describes contemporary global summitry and how summitry today can be used to achieve both progress and stability in this most important of great power relations.

Now I must say I am a fan of Rudd – far more knowledgeable about, and interested in, international relations and international policy than most contemporary leaders. He has written a serious piece on US-China relations. Shining a light on the new leaders and what this new leadership should examine probably would have been enough for me but in addition he has become a strong proponent for advancing the US-China relationship by a regular series of summits between the leaders – Xi Jinping and Barack Obama. While I am never one to ‘pooh pooh’ summit advocacy, I think our former Australian leader has missed the contemporary structure of summitry and the effective means to influence contemporary regional and international stability.

So let’s drop back for a moment and examine global summitry. Now at the global summitry project here at the Munk School of Global Affairs the working definition of global summitry is:

The variety of actors – international organizations, transgovernmental networks, states and select non-state entities – involved in the organization and execution of global politics and policy. Global summitry is concerned with the architecture, the institutions and most critically the political and policy behavior and outcomes in global governance.

This is not your old style summitry. It is not primarily about the “great man” theory of summit leadership – you know key leaders gazing intently across from each other determined to avoid conflict, or advance a new strategic direction – be they Chamberlain and Hitler or Kennedy and Khrushchev or a little closer to Rudd’s theme – Mao and Nixon .

I have pressed the case in this Rising BRICSAM blog and will again in the new ejournal Global Summitry we are about to launch at the Munk School of Global Affairs that to look at these leaders summits alone, referring here particularly to the apex of such summitry today – the informal and now annual G20 Leaders Summit – misses the better part of the structure of international governance. Today a significant structure underpins and motivates summitry. I call this view the ‘Iceberg Theory of Global Governance‘. In the case of the G20 there are: the periodic meetings of the finance and central bank governors; the sherpa meetings – the personal representative of the leaders – where the agendas are put together, the meetings of the Working Groups – and there are more than a few, the meetings and reports from the traditional IFIs including, the IMF, World Bank, others, the transgovernmental regulatory organizations like the FSB, BCBS – you get the picture – a large largely unstructured structured institutional network that feeds the periodic meetings and moves the agenda forward to completion in many circumstances.

I think Rudd is rather too enamored with the old frame of global summitry. Rudd urges that the United States choose the following course:

A third possibility would be to change gears in the relationship altogether by introducing a new framework for cooperation with China that recognizes the reality of the two countries’ strategic competition, defines key areas of shared interests to work and act on, and thereby begins to narrow the yawning trust gap between the two countries. Executed properly, such a strategy would do no harm, run few risks, and deliver real results. … A crucial element of such a policy would have to be the commitment to regular summitry.

As he points out there are many informal initiatives between the two great powers, “[b]ut none of these can have a major impact on the relationship, since in dealing with China, there is no substitute for direct leader-to-leader engagement.” As a consequence Rudd urges:

The United States therefore has a profound interest in engaging Xi personally, with a summit in each capital each year, together with other working group meetings of reasonable duration, held in conjunction with meetings of the G20, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, and the East Asia Summit.

But the governments also need authoritative point people working on behalf of the national leaders, managing the agenda between summits and handling issues as the need arises. In other words, the United States needs someone to play the role that Henry Kissinger did in the early 1970s, and so does China.

Now Rudd suggests that for an agenda the leaders need to then take one or more issues that are currently bogged down and “work together to bring them to successful conclusions” and he suggets tackling the stalled Doha Round issues, climate-change negotiations, nuclear nonproliferation or specific outstanding items on the G20 agenda. Rudd concludes:

Progress on any of these fronts would demonstrate that with sufficient political will all around, the existing global order can be made to work to everyone’s advantage, including China’s.

Now Rudd doesn’t end there but has suggestions for the regional dimension including obviously the island disputes and a protocol to address incidents at sea; and on the bilateral matters Rudd urges that military-to-military contact be upgraded and the talks should be insulated from the ups and downs of the US-China relationship.

Now there is value in urging bilateral summits. But let’s not turn these current global summit efforts into a G2 – there is much suspicion already around the high table of an implicit bilateral power consortium. An explicit effort of this sort could only undermine collective summitry efforts. So let’s avoid China and the US dealing as a central agenda with the global agenda of the G20 or the EAS Summit. And let’s build this new summit network off of let’s say the bilateral S&ED (Strategic and Economic Dialogue). Here groups tackle bilaterally through a vast network of national officials and ministries the bilateral issues that raise tensions and conflict in US-China relations.

I have heard that President Obama, following the G20 Toronto Summit, complained that he was meeting all the same leaders from one summit to another. I hope his officials pointed out that that was exactly the point. So for both Obama and Xi, the G20 or APEC or EAS remains part of global governance structure that is needed for collective discussions and decision-making – leave the bilateral to the bilaterals.

And as for the military-to-military discussions I suspect it still a vain hope to expect these meetings to be insulated from the competitiveness and rivalry that remains an element of the great power relationship. However, I would think the building of a more structured and regularized network dedicated to the S&ED – its tasking and summit meetings – could in the long run insulate the military discussions from the displays of political displeasure.

There is clearly a case for global summitry for the US-China relationship it is just not the model Rudd suggests.

Image Credit: www.heraldsun.com.au