I’ve just had the good fortune to return from Oxford University where I spent several very pleasant days examining with experts and others the health and direction of global governance. This almost annual Princeton University Workshop is a highly satisfactory partnership of the Council on Foreign Relations and Stewart Patrick, Princeton University and John Ikenberry, The Stanley Foundation, President Keith Porter and Program Director Jennifer Smyser, and ‘moi’ of the Global Summitry Project at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto.

A Multilateral World Is Well – Complicated! And There is No Roadmap

Now evidently – from the image above – this is not the first speech that US President Obama has given at West Point. Here then is an earlier portrait of the President there – the black hair obviously is a dead give away. Still the President’s commencement address this year has been seen as an opportunity for the President to outline his Administration’s foreign policy and the rationale in how he and his officials have implemented US foreign policy.

A World in Flux II

It’s a pleasure to review work of colleagues seriously grappling with the contemporary world order. Back in March I reviewed Bruce Jones’s examination of the global order at the point just prior to the publication of his new book – Still Our To Lead. Since that time a number of other close colleagues have had a chance to weigh in on his world view and I thought I’d double back to look at their perspectives and revisit my own.

Struggling with World Order

Who said geopolitics went away? Well a number of international relations experts imply this in their various announcements that geopolitics has returned. One of those most loudly trumpeting this view is Walter Russell Mead, the Editor-at- Large of the American Interest. In his most recent piece in Foreign Affairs he declares:

But Westerners should never have expected old-fashioned geopolitics to go away. They did so only because they fundamentally misread what the collapse of the Soviet Union meant” But geopolitics never went away, notwithstanding there was a great deal of attention focused on the global economy – particularly in the light of the 2008 global financial crisis.

Struggling with Change in Great Power Relations – An Addendum

It is a little like having a stomachache. The United States is struggling to operationalize its diplomacy in the ever changing landscape. And its finding it hard to digest the changes without feeling rather sick.

So at the end of his 4-nation Asian trip President Obama pushed back against those who have grown increasingly critical of his foreign policy towards Russia, China and Syria, if not others. In his reaction Obama suggested that his policy was a game of what Americans call ‘small ball’:

You hit single, you hit doubles; every once in a while we may be able to hit a home run.

The Return of Great Power Territorial Ambition?

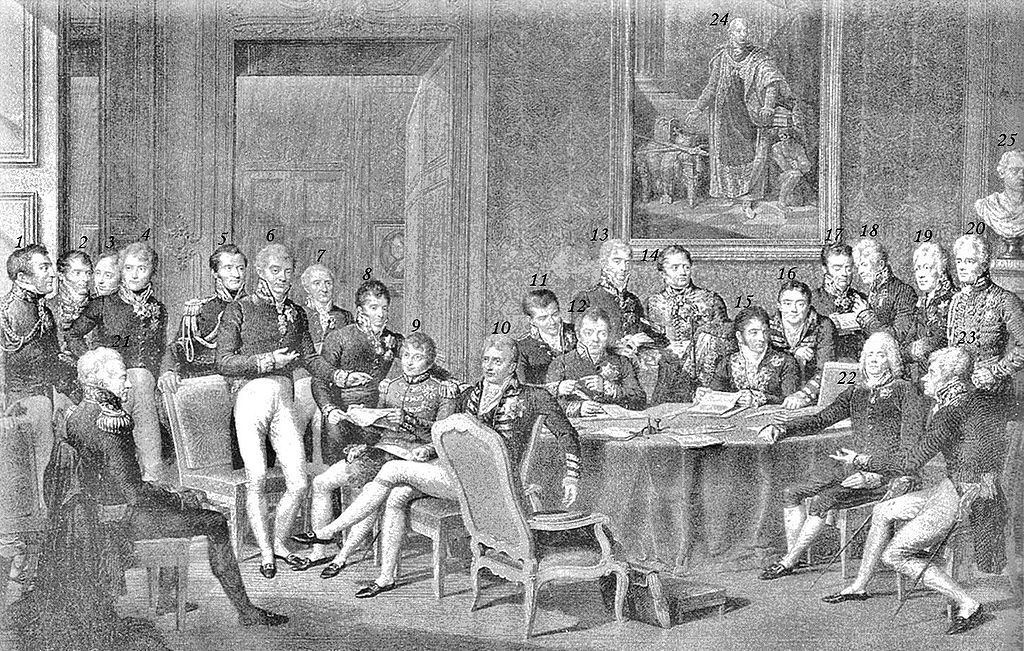

Great power rivalry has forcefully reappeared. It is a jolt for anyone that follows international governance to watch the Russian actions in the Crimea and to hear the assertions and rationalizations by Russia’s President Putin concerning Russian annexation of the Crimea.

A World in Flux

I was going over Richard Rosecrance’s explication on UCTV of his his latest international relations thesis: The Resurgence of the West: How a Transatlantic Union Can Prevent War and Restore the United States and Europe. His analysis demands comment. But not right at this moment.

A Serious Setback – The G20 ‘Concert’ Wounded

While we all have been debating whether the Russian intervention in the Crimea warranted expelling Russia from this or that organization, a very serious wound has been inflicted on global summitry.

Its Not the G8 – But the BRICS and even the G20

I was caught by the discussion in this morning’s New York Times in the “Room for Debate” section. At the NYT site several old friends from global summitry analysis and a few new acquaintances set out their opinions on whether to kick Russia out of the G8 or not.

The News from Down Under – Steady but with some Fluff

The G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bankers (Ministers) met this weekend in Australia to further develop the G20 Brisbane Action Agenda. They released, mercifully, a short communique that identified, whether stated or not, their continued measured efforts to achieve in G20-speak ‘strong sustainable and balanced growth”. This meeting is just one piece in a continuing effort to provide policy coordination for the G20 – and a step along the road to the completion of the Brisbane Action Plan.