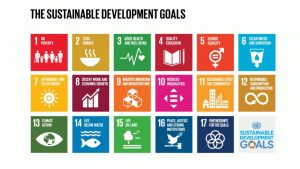

As I mentioned in past Posts here at Alan’s Newsletter, one particular research focus for the Global Summitry Project (GSP) is the effort to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals ( SDGs). You can see some of the activity at the GSP website and specifically at: “Strengthening Global Governance Activity and Reaching the SDG Goals”. A word of nomenclature here. The UN often refers to these goals as Agenda 2030. As part of this research focus, we have been building a Special Issue of the e-journal Global Summitry on achieving the SDGs. I have not gone as fast as I’d like and ferreting out folks interested in the SDGs has proven to be somewhat more difficult than I originally assumed.

As I mentioned in past Posts here at Alan’s Newsletter, one particular research focus for the Global Summitry Project (GSP) is the effort to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals ( SDGs). You can see some of the activity at the GSP website and specifically at: “Strengthening Global Governance Activity and Reaching the SDG Goals”. A word of nomenclature here. The UN often refers to these goals as Agenda 2030. As part of this research focus, we have been building a Special Issue of the e-journal Global Summitry on achieving the SDGs. I have not gone as fast as I’d like and ferreting out folks interested in the SDGs has proven to be somewhat more difficult than I originally assumed.

But there are folks out there for sure. And, indeed, I came across ‘one good soul’, Peter Singer and his Substack, Global Health Insights. Now, I am no global health expert but Peter has dedicated much attention in his Substack to the subject and has focused on the achievement of the SDGs as being part of his focus on the global effort to eliminate disease, end poverty and bring a global improvement in health care.

As it turns out there is a long trail of serious effort on his part to examine the improvement in global health but not surprisingly he, like many others, have expressed recently a not unreasonable hint of dismay in the overall effort to achieve the SDGs. Here, then, is a relatively recent post in ‘Global Health Insights’, “Replace the SDGs with the GSDs” expressing the concern:

Halfway through Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) period, only 15% of the SDGs are on track. Universal Health Coverage, for example, is going at one-half the pace needed to reach the 2030 targets.

It is a sensitive time after all. First, the SDG Summit at this year’s opening of the UN General Assembly (UNGA) has come and gone and notwithstanding the hortatory UN efforts, especially by the Secretary General, there does not seem to me at least to be any greater energy at the member level to dig in on the SDGs nor accelerate the pace of achieving the 17 goals. And as we look forward we see that a second UN summit is drawing closer – this the Summit of the Future. This Summit will occur at the next UNGA opening that is this coming September. Much effort is promised but I am unconvinced that finalizing the ‘Pact for the Future’ a major deliverable of the UNGA in September is likely to alter substantially the multilateral effort notwithstanding the UN view that the Pact and Summit will bring the following:

The result will be a world – and an international system – that is better prepared to manage the challenges we face now and in the future, for the sake of all humanity and for future generations. … The Summit of the Future will create the conditions in which implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development can more readily be achieved. It will do so by building on the outcome of the 2023 SDG Summit. In addition, it will result in improvements to international cooperation that enable us to solve problems together. We will be able to harness new opportunities for the benefit of all, not just the few, and manage the risks more effectively. Every proposal offered by the Secretary-General for consideration at the Summit of the Future will have demonstrable impacts on achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Well, I hope so, but the encouragement from the UN in the end is not the answer. As Peter says: “The SDGs are gained or lost not in Geneva or New York but in countries.” That insight needs to be kept in mind by all of us. There has been much recent attention directed to serious efforts but at the local level – at the city level and the regional level as well at the non-state level – all detailing efforts to advance the SDGs. Ultimately, however, the primary effort and likely acceleration of the SDGs will in the end have to come from the national level if we are to see a closing of the gap between what has been achieved and what needs to be achieved to reach the goals. I suspect the attention to the substate and non-state level is sadly a result in part of the limited action – where it counts – at the national level. The US is but one unhappy example but there are many others.

So what does Peter Singer target. As he urges:

To speed up the SDGs, the world needs three things: implementation, implementation, implementation. In short, we need to replace the SDGs with the GSDs: Get Shit Done! (OK, I said ‘replace’, but I meant ‘refocus’ or ‘supplement’ the SDGs with the GSDs. And for diplomatic purposes, we can use the term ‘get stuff done.’)

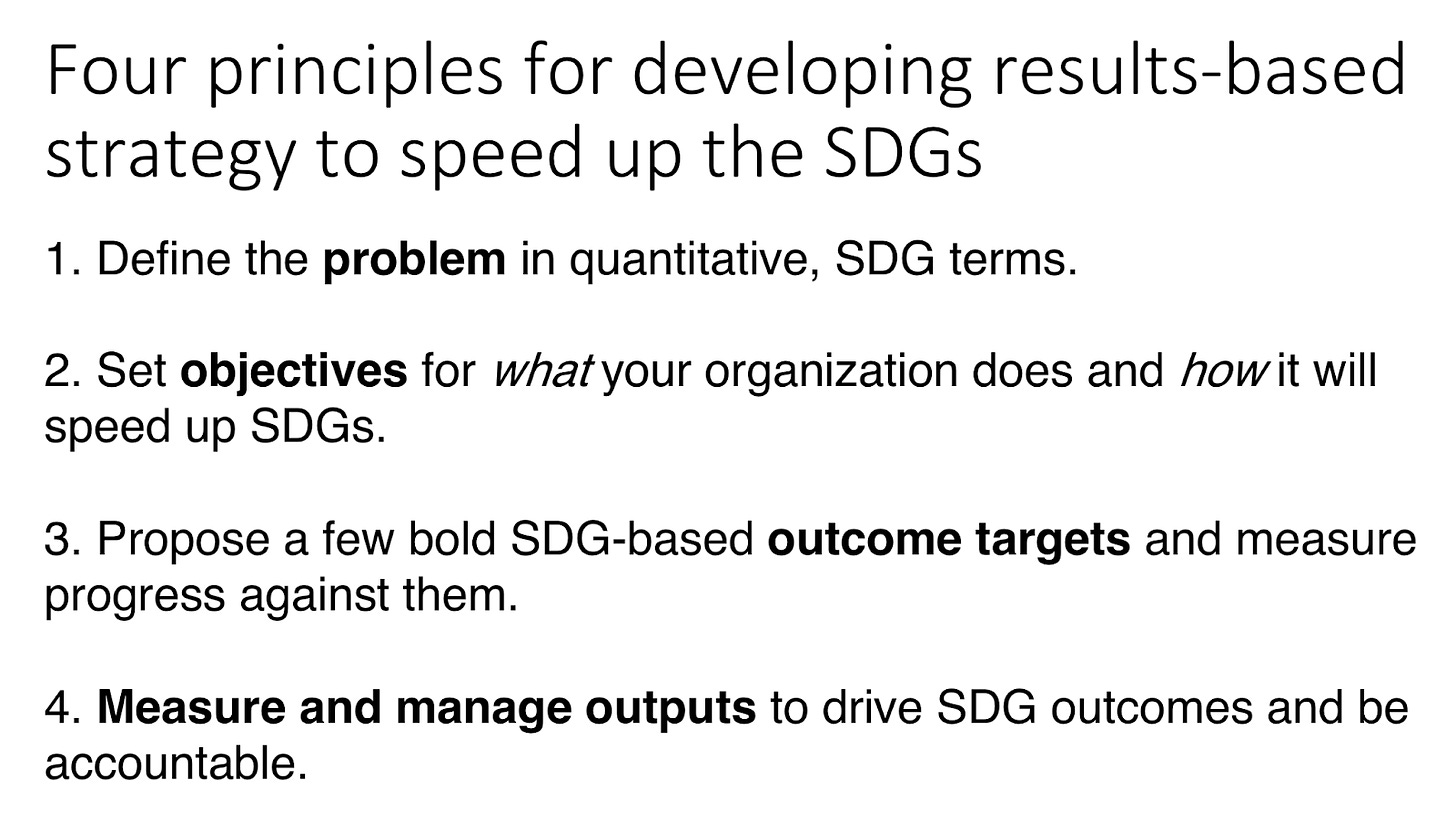

More recently Peter has set out a way forward in this recent table:

You can also see that Peter turns the quantitative aspect of the SDGs into a positive and that strikes me as a crucial part of his approach. As he explains:

Measuring and managing impact using results-based strategy is an essential part of the GSD (Get Sh*t Done) approach to speeding up SDGs. To read more about this approach, please see here. … The trick in strategy is to focus as much on the “how” as the “what.” WHO’s strategy is built around five ‘Ps’: Promote, Provide, Protect, Power and Perform. The first three represent the ‘what’ (and correspond to the triple billion targets), the fourth and fifth represent the ‘how’, as shown below.

I shall return to Peter Singer’s approach in subsequent Posts but I wanted to at least get the big picture out. Achieving the SDGs is a demanding problem.

This week I, and just about everybody else holding some interest in sport, or at least in innovative commercials were distracted by the events leading up to, and including, the 58th Super Bowl. Notwithstanding the quickening approach of this Super Bowl Sunday, however, I was drawn to an examination by a number of experts for the Brookings Institution of the US-China relationship.

This week I, and just about everybody else holding some interest in sport, or at least in innovative commercials were distracted by the events leading up to, and including, the 58th Super Bowl. Notwithstanding the quickening approach of this Super Bowl Sunday, however, I was drawn to an examination by a number of experts for the Brookings Institution of the US-China relationship.

Yup, a little late in the weekend it is. But then for some Monday is a holiday. Mea culpa, but I was deep into completing a draft chapter for a yet to appear volume – which, in fact is scheduled to be released by 2025. The publication year, by the way, is important. My chapter will be part of a planned edited volume by Edward Elgar Publishing. There will be many chapters, so I am told, that will review and analyze the G7. It will do so on the 50th anniversary of the initiation of the G7 Leaders Summit. Yup, Rambouillet, the acknowledged first G7 Leaders Summit – it was actually, the G6 – France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US at that moment in time – met in 1975. All the chapters, I suspect, will cover aspects of this ‘First Informal’, the G7, and, I suspect, the other Informals as well – that is the G20 and the BRICS.

Yup, a little late in the weekend it is. But then for some Monday is a holiday. Mea culpa, but I was deep into completing a draft chapter for a yet to appear volume – which, in fact is scheduled to be released by 2025. The publication year, by the way, is important. My chapter will be part of a planned edited volume by Edward Elgar Publishing. There will be many chapters, so I am told, that will review and analyze the G7. It will do so on the 50th anniversary of the initiation of the G7 Leaders Summit. Yup, Rambouillet, the acknowledged first G7 Leaders Summit – it was actually, the G6 – France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, US at that moment in time – met in 1975. All the chapters, I suspect, will cover aspects of this ‘First Informal’, the G7, and, I suspect, the other Informals as well – that is the G20 and the BRICS.

Doing some quick catch up on the APEC Summit that was held between November 11th and 17th in San Francisco. The main event, as it turned out, was the much discussed bilateral summit between China’s Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden. While the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) meetings to receive some attention – more for what didn’t happen than what was secured – the APEC gathering activity was dominated by US-China Bilateral Summit and there was some attention paid to the other bilateral Summit of note that between President Xi and the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

Doing some quick catch up on the APEC Summit that was held between November 11th and 17th in San Francisco. The main event, as it turned out, was the much discussed bilateral summit between China’s Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden. While the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) meetings to receive some attention – more for what didn’t happen than what was secured – the APEC gathering activity was dominated by US-China Bilateral Summit and there was some attention paid to the other bilateral Summit of note that between President Xi and the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.