Though it was heartening to see the Presidential debate this past week with a strong performance by Vice President Kamala Harris, it was disheartening to see that Donald Trump remains a major force in US politics and still a strong contender notwithstanding some of his wild statements and his conspiracy theory assertions. While the event highlighted the ‘weirdness’ of Donald J Trump, the candidate, the game is not yet won. We may yet see him reoccupy the White House. Such an outcome would threaten the alliance(s) system, global trade and continuing US presence in the current multilateral system driven by Trump’s transactional model of US foreign policy behavior.

Trump’s return would likely drive current US foreign policy ‘over the cliff’. But changes have been underway for some time and many of them are weakening the multilateral system built over many decades. Many foreign policy analysts have focused on the structural elements – notably the decline in the international measures of power of the United States and its impact as a result on the global order. I was struck by a letter titled, “Muster Global Majorities” prepared by Mark Malloch-Brown. This is just one of nine requested by FP to greet a new US president. Now, Malloch-Brown was the former deputy secretary-general of the UN well aware of the multilateral system and he targeted the decline of the US:

But whoever prevails on Nov. 5—and congratulations, by the way—this will not change the much deeper shifts underway in the distribution of global power and values alignment that are now surfacing at the U.N. and its Bretton Woods cousins, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). They have seen an approximate quadrupling of membership since their post-World War II founding; a more than tripling of global population; and a global GDP that is more than 10 times bigger.

But you must see there is a global shift underway, and the United States, more than ever, is not an unchallenged No. 1 but rather a precarious first among equals in a multilateral system and which in responding to wider intellectual and political change in the world resents any claim to monopoly leadership. As Shakespeare observed in his great play on succession and power, Henry IV, Part 2: “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

Malloch-Brown in his letter, in fact, is pointing to two evident declines: the decline in power of the US in the context of the global system, the structural elements with the rise of China and with the emergence of a number of the Large Emerging Powers, the likes of India, Brazil, Indonesia and more. But the decline is also evident from a diminishment in US leadership in the global order, the behavioral aspect of any analysis.

While there is a relative decline in the power dimensions for the United States, it is the decline in policy leadership that is in some ways most evident. Take trade. As Alan Beattie has written just recently in the FT article entitled, “Can Globalization Survive the US-China Rift”:

Multilateralism is weak. The US is undermining the WTO by citing a national security loophole to break rules at will. The EU won a case against Indonesia over its nickel export ban, but the WTO’s dysfunctional dispute settlement system has delayed compliance.

But this does not mean regional or geopolitical trading blocs will start setting the rules of trade instead. The US talks a good game about building alliances, but the political toxicity of trade deals in Washington stops it offering market access to incentivise countries to join. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the US’s main initiative in the Asia-Pacific, is widely regarded as all stick and no carrot.

Rather than a continued reliance on the multilateral rules and the WTO, the multilateral trade institution – of which the US is one of the primary creators – responsible for managing trade and trade friction, the United States has chosen to neuter the global trade rules by collapsing the trade dispute mechanism of the WTO. The US has turned away as well from promoting freer trade and free trade agreements and has come to rely more and more on protectionism. As pointed out by Bob Davis in his FT piece, “How Washington Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace Protectionism”, he described the US turn to protectionism:

… the president [Biden] made a decision that upended decades of Democratic White House rule. He ordered heavy new tariffs on Chinese imports of high-tech items and continued the massive tariffs he inherited from his Republican predecessor.

The significance of the moves—and the challenge that it presents to Biden’s successor—was obscured by the roller-coaster news cycle. But it bears noting: The Biden administration is the first since at least President John F. Kennedy’s time to fail to negotiate a major free trade deal, instead embracing tariffs. Even Trump, the self-proclaimed “Tariff Man,” concluded a significant free trade pact when he replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement with a U.S.-Mexico-Canada deal (USMCA), which toughened rules on auto imports but established liberal rules on digital trade. He also negotiated a smaller digital agreement with Japan.

The turnabout is emblematic of a broader change in the U.S. economic and political thinking that is unlikely to be reversed under either a President Trump or Harris. The era of hyperglobalization, which began around 1990 and saw global trade jump by 60 percent in 20 years as supply chains spread across the earth like spiderwebs, has come to an end. We are now in an era of growing protectionism, and as trade growth has stalled, the United States and many other advanced economies have hiked tariffs and begun subsidizing industries that they view as critical to their well-being.

The turnabout with an increasing reliance on tariffs and a more full throated rise of US protectionism in fact ties the US, that is US economic policy to its political-security policy and actions. Davis makes the pointed linkage today between the two for US policy action:

Peter Harrell, the White House’s former senior director for international economics, said the change marks a fundamental rethinking of U.S. trade policy. “We are in an era of geopolitical competition with China,” he said. “That means we aren’t going to accord China the same trading privileges and rights” accorded to allies—despite World Trade Organization requirements to treat members equally.

It boils down to the fact that the economic juice [from cutting tariffs] was not worth the political squeeze,” said Evan Medeiros, a Georgetown University China expert who had been an official on Obama’s National Security Council.

In the second part of its decision, the administration ramped up some tariffs to block Chinese imports in areas where the United States was spending billions of dollars on subsidies to create or strengthen a domestic industry.

Tariffs were quadrupled to 100 percent on Chinese electric vehicles this year, as [Lael] Brainard had advocated, doubled to 50 percent on Chinese semiconductors and solar cells, either this year or next, and tripled to 25 percent on EV batteries this year. Even low-tech Chinese syringes, which had previously been shipped duty-free, now face 50 percent tariffs as a spur to boost domestic production.

The primary reason for the U.S. turn to protectionism is the growing economic and military challenge from China. But it also reflects a profound change in ideology: The gains from trade—lower prices, overall improvements in living standards, greater competition—are no longer seen by many political leaders as worth the downsides in the loss of manufacturing jobs, dependence on imports from adversaries such as China and Russia, and political polarization. The Trump administration, packed with anti-free traders, gave a big push to this neo-protectionism; the Biden administration has confirmed and deepened the shift.

The bottom line is that geopolitical tensions, particularly the deep US-China competition, has undermined US commitment to a multilateral system that the US was a principal architect in creating and maintaining over many decades. This outcome to date is deeply troubling.

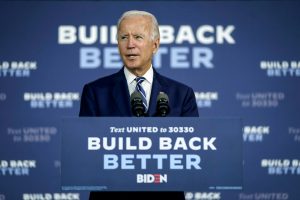

Image Credit: CNBC

So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous

So, I was ruminating a bit on the question of US diplomacy coming off of the previous  With just over 70 days until the US election, and with the certainty now of a new 47th President – either Harris or former President Trump – it is not surprising that analysts are scrambling to assess the current US foreign policy course and eyeing its new possible directions.

With just over 70 days until the US election, and with the certainty now of a new 47th President – either Harris or former President Trump – it is not surprising that analysts are scrambling to assess the current US foreign policy course and eyeing its new possible directions.

It’s rather foolish to believe that even a ‘bullet wound’ would alter Donald Trump. His speech accepting the nomination for the Republican Party on Thursday night – over 90 minutes – proved that. What you see is what you get. But let me reflect for a moment on the consequences for Trump, and the political system, of this attempt on his life. Its impact it seems on American politics, and more particularly on the Trump third presidential run – well, at least for the moment, appears rather negligible. As Susan B. Glasser of

It’s rather foolish to believe that even a ‘bullet wound’ would alter Donald Trump. His speech accepting the nomination for the Republican Party on Thursday night – over 90 minutes – proved that. What you see is what you get. But let me reflect for a moment on the consequences for Trump, and the political system, of this attempt on his life. Its impact it seems on American politics, and more particularly on the Trump third presidential run – well, at least for the moment, appears rather negligible. As Susan B. Glasser of

We are definitely in the midst of Global Summitry gatherings. With the BRICS Summit just recently ended, we are deep into the G20 weekend gathering in New Delhi. So much commentary has accompanied these summitry gatherings. But I caution casual observers and readers: there are way too many assessments and conclusions drawn by all those folks that unfortunately barely pay attention to Global Summitry through much of the year. You can see this in the various ‘hair on fire’ commentaries in the assessments and consequences of the actions of key players in both the BRICS and now especially with the G20. Too many declarations of the G20 demise; firm conclusions that China and Russia would block any consensus statement that sought to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine; the fragmentation of global summitry with the rise of the BRICS plus and the demise of the G20 with leaders from Russia and China choosing to absent themselves from summit.

We are definitely in the midst of Global Summitry gatherings. With the BRICS Summit just recently ended, we are deep into the G20 weekend gathering in New Delhi. So much commentary has accompanied these summitry gatherings. But I caution casual observers and readers: there are way too many assessments and conclusions drawn by all those folks that unfortunately barely pay attention to Global Summitry through much of the year. You can see this in the various ‘hair on fire’ commentaries in the assessments and consequences of the actions of key players in both the BRICS and now especially with the G20. Too many declarations of the G20 demise; firm conclusions that China and Russia would block any consensus statement that sought to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine; the fragmentation of global summitry with the rise of the BRICS plus and the demise of the G20 with leaders from Russia and China choosing to absent themselves from summit. So, the International Studies Association (ISA) just concluded in Montreal

So, the International Studies Association (ISA) just concluded in Montreal