Current diplomatic activity, especially recent visits by senior U.S. officials to China underline the still difficult relations among the major powers. William Burns, the current CIA head, earlier this month described the more tense relations among the major states in international relations in the annual Ditchley lecture:

Current diplomatic activity, especially recent visits by senior U.S. officials to China underline the still difficult relations among the major powers. William Burns, the current CIA head, earlier this month described the more tense relations among the major states in international relations in the annual Ditchley lecture:

The US and its allies have to adapt to a world of permanently contested primacy. The post-Cold War dominance of the US drove the world more broadly towards democracy and free markets. …Those trends have now solidified into current reality with strategic competition with China and Russia’s war in Europe, one representing the challenge from a rising power, and the other showing that a declining power could pose a different type of threat. The post-Cold War era is definitively over and the US is no longer the only big kid on the block.

Here at Global Summitry Project (GSP), we pay ‘large’ attention to the policy and to the process in the Global Order. We are also ‘driven’ to comment on many of our colleagues, particularly those drawn to a ‘Realist’ perspective in international relations. Many colleagues are called on to target and explain their framing of international relations from a great power dynamic. As a result I, and many other colleagues, expend much analytic energy on all these Realist views that continue to focus on the ‘structure’ of major power relations and its consequences. These Realists dedicate much energy in describing the distribution of power among the major and lesser powers. There is a strong commitment to explaining international outcomes by targeting the international structure and assessing whether the Global Order sets up as a unipolar, bipolar or multipolar order. Note, for instance, the recent article inForeign Affairsby IR experts, Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth, both of Dartmouth, that tackle in “The Myth of Multipolarity: American Power’s Staying Power”, the decline in power of the United States but the continuance in their view of U.S. unipolarity, of a sort, nonetheless. As they write:

Now, American power seems much diminished. In the intervening two decades, the United States has suffered costly, failed interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, a devastating financial crisis, deepening political polarization, and, in Donald Trump, four years of a president with isolationist impulses. All the while, China continued its remarkable economic ascent and grew more assertive than ever. To many, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine sounded the death knell for U.S. primacy, a sign that the United States could no longer hold back the forces of revisionism and enforce the international order it had built. … Yes, the United States has become less dominant over the past 89 years, but it remains at the top of the global power hierarchy—safely above China and far, far above every other country. No longer can one pick any metric to see this reality, but it becomes clear when the right ones are used. And the persistence of unipolarity becomes even more evident when one considers that the world is still largely devoid of a force that shaped great-power politics in times of multipolarity and bipolarity, from the beginning of the modern state system through the Cold War: balancing. Other countries simply cannot match the power of the United States by joining alliances or building up their militaries. … What is at issue is only the nature of unipolarity—not its existence. (78)

But much of this expert focus is – from my perspective – misplaced, or at best, confusing if not conflating. While structure has its place in understanding global order relations – stability, conflict, global governance progress – or any other global order issue, the central concern of global order relations has to be – in my humble opinion, on the process and policy of the major actors – states, substates or non-state actors. It is not, in the end, notwithstanding the Realists, about unipolarity, bipolarity and multipolarity, the structural configuration of the Global Order. It is rather about unilateral, plurilateral or multilateral policy making. Moreover, it would be very helpful indeed for colleagues to stop confusing all of us by intermixing structural configurations – unipolarity, bipolarity and multipolarity with policy and process groupings – unilateral, bilateral, plurilateral, or possibly minilateral, and the ‘holy grail’, multilateral.

Now that we have that ‘out of the road’ for the moment at least, let’s focus on the difficult terrain that we see in international relations. It starts with the undermining of the rules, principles and norms that to one degree or another have laid a base for international conduct. The recent Council of Councils gathering by the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) focused on this in their most recent gathering:

The lack of global solidarity is worrying. The ordering principle of territorial sovereignty could no longer be respected, and the international ambivalence over the invasion of Ukraine is a warning sign for an inability to act collectively to mitigate global challenges. One participant argued that upholding the sanctity of borders is in everyone’s interest, particularly smaller states. While several participants raised the West’s double standard for only caring about universal principles of sovereignty in Europe, others suggested that the West’s track record in previous conflicts was no excuse to react with ambivalence in this case. Several participants agreed that the only way to respond to the violation of these norms is to give enough support to Ukraine to ensure Russia loses. They argued the world should demonstrate that the invasion of sovereign territory and wars of aggression will not be tolerated.

We will return to the rules-based international order (RBIO), and what it is, or isn’t in the future. But for now let’s target the most difficult current bilateral relationship in the Global Order, the US-China policy efforts. Why such a focus. Well, from a global order point of view, I think my CWD co-chair, Colin Bradford, Senior non-resident Fellow at Brookings has expressed it well to another colleague:

The CWD is not just about China, but centrally about strengthening global governance to address systemic global challenges with China crucially involved and not excluded or diminished. A promising way [we hope is] to strengthen the G20 as a means of strengthening global governance for the future.

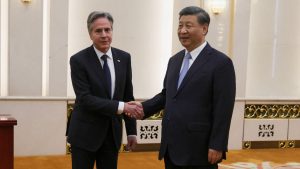

But on the US-China side recently there has seemingly been serious diplomatic activity. What has occurred is a series of visits by senior American officials. First there was the visit of Secretary of State Antony Blinken following his cancellation of an earlier trip to China due to ‘balloongate’. This was followed by Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen and most recently three days of intense discussion on climate matters by climate envoy John Kerry with his counterpart in China Xie Zhenhua. In each instance modest advances seem to have occurred. For instance Sha Hua in the WSJ identified John Kerry’s eagerness to move forward on the bilateral climate discussions:

Kerry said he and his Chinese interlocutors were already discussing the next two sets of meetings ahead of the upcoming climate summit in Dubai at the end of the year. Points of further discussion, he said, include new emission goals for 2035 and ways to reduce emissions of methane and other non-carbon dioxide emissions. China’s use of coal, Kerry said, remains a contentious issue.

Secretary Yellen also described forward movement reported in Al Jazeera:

Yellen said on Sunday the objective of her visit was to establish and deepen ties with China’s new economic team, reduce the risk of misunderstanding and pave the way for cooperation in areas such as climate change and debt distress. … No one visit will solve our challenges overnight. But I expect that this trip will help build a resilient and productive channel of communication,” she said, adding that she expected increased and more regular contact at the staff level.

But these forward steps, though modest, it seems, failed to assuage all. There was much discussion back in the U.S. that no agreements had been secured. In particular there was loud concern expressed that Kerry had failed to achieve a new US-China climate agreement and there was much made of the statement by Xi Jinping reported by Sha Hua and others that China would follow its own path to emission reductions:

In remarks to that gathering, Xi reiterated China’s goals to see its climate-warming emissions peak before 2030 and become carbon neutral before 2060. But he underscored that his government would proceed on its own timetable despite pressure from the Biden administration to accelerate the time frame.

Even more pointedly the earlier diplomatic efforts of Secretary of State Blinken came in for strong criticism including from Republican members of Congress. Notably, there was vocal criticism by Rep. MIke Gallagher, Chairman of the new Select Committee on China:

I’m concerned that we’re seeing the revival of diplomatic and economic engagement as the central part of our strategy with China, … The reason this is misguided in my opinion is that we’ve tried this for 20 years and it hasn’t worked.

Gallagher signaled this early in the Biden Administration effort to re-establish communication channels. Gallagher, in an opinion piece on June 14th for the WSJraised the spectre of what he called, ‘zombie engagement’:

This is the trap of zombie engagement. It almost always places the burden of “improving” relations on the U.S. rather than demanding that Beijing adjust its malign behavior. We give up the farm simply to get to the negotiating table. Once we’re there, we’re beholden to an entirely new process of concessions because of the pressure to present “deliverables.” While we build guardrails for ourselves, the Communist Party builds fast lanes to achieve its long-term objectives.

Gallagher, a significant Republican foreign policy figure in Washington, appears to have turned back the clock: current modest diplomatic effort has been harshly criticized as a part of the ‘failed’ engagement strategy of an earlier period.

So where are US-China relations? And how do we understand current global order relations? Tuning in to Washington would leave one highly concerned over the growing U.S.-China tensions. But outside the ‘Washington world’, a modest improvement in diplomatic relations may well best characterize the state of relations.

We will, naturally, continue to follow and report on diplomatic and security actions.

The following is a Substack Post from Alan’s Newsletter uploaded on July 21, 2023. Feel free to subscribe at: https://substack.com/@globalsummitryproject

Image Credit: CNN

So, the International Studies Association (ISA) just concluded in Montreal

So, the International Studies Association (ISA) just concluded in Montreal

So, the

So, the