Opinion and analysis writing often seems to come forward in ‘waves’. It is almost never just one piece but a veritable series of similar narrations that seeks to identify the trends. This wave-like writing certainly is evident when it comes to US foreign policy making and in particular the rising tensions between the two leading powers – the United States and China. There was a first wave of ‘New Cold War’ articles, that as I suggested along with some of my V20 colleagues seemingly impacted partisans of both Parties in the United States. Then, there was the wave US-China trade war tensions. And now we see the current wave in the ‘Rising US-China’ tensions and the return to a view that this may indeed be a new sorta ‘Cold War’ and dire predictions of decoupling between the two leading economies and the ‘deer in the headlights’ of US allies trying to avoid choices between the two.

This newest wave of US-China tensions has been orchestrated in part by the Trump Administration with speeches from senior officials William Barr, the Attorney General, Robert C. O’Brien, National Security Advisor, Christopher Wray, the Director of the FBI, Mark Esper Secretary of Defense and, finally with the icing on the cake the speech by Michael Pompeo the current Secretary of State at a highly significant location – the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum at Yorba Lind, California.

It is interesting that these declarative words all began with the Donald Trump’s actions – the chaos, the denigration of multilateralism, the strong-arming of allies and the threats to end key alliance relations of the liberal order – NATO, US- Japan and US-Korea security treaties. While these initiatives and threats heralded Trump’s America First policy they have been superseded most recently with the targeting of China. It reflects, one suspects, the ‘Hail Mary’ approach that Trump seems to have chosen with falling numbers on his reelection. It is China ‘all the time’, by these officials, attacks on the Communist Party of China and even the targeting of regime change by these US officials. Additionally, and I don’t think prematurely US foreign policy analysts are at the same time attempting to anticipate a foreign policy under a Biden Administration. But we’ll save that examination for another moment.

Meanwhile the language is barely restrained . As my CSIS colleagues Scott Kennedy and Matthew Goodman conclude in a recent post:

Through a series of speeches and tough actions, the Trump administration has clearly signaled that it views a Xi Jinping-led China as an existential threat to the West, and hence, is trying to mobilize its friends and allies to form a united front against Beijing.

Here is William Barr, the Attorney General of the United States describing China and its current ambitions in a speech he delivered on July 16th:

… that is, the United States’ response to the global ambitions of the Chinese Communist Party. The CCP rules with an iron fist over one of the great ancient civilizations of the world. It seeks to leverage the immense power, productivity, and ingenuity of the Chinese people to overthrow the rules-based international system and to make the world safe for dictatorship.

The objective is according to Barr, clear:

The People’s Republic of China is now engaged in an economic blitzkrieg—an aggressive, orchestrated, whole-of-government (indeed, whole-of-society) campaign to seize the commanding heights of the global economy and to surpass the United States as the world’s preeminent superpower.

And, the dire views of Barr are only amplified, indeed ‘accelerated’ a now favored term in this ‘Age of the pandemic’ by Mike Pompeo:

But I have faith we can do it. I have faith because we’ve done it before. We know how this goes. I have faith because the CCP is repeating some of the same mistakes that the Soviet Union made – alienating potential allies, breaking trust at home and abroad, rejecting property rights and predictable rule of law.

And as pointed up above the location of the Pompeo speech was no accident. It is the Nixon library – the archive of the President that set in motion along with his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, the dramatic alteration of US policy toward Mao’s China – one of the seminal diplomatic events of any President in the post WWII period. And why deliver the speech there? Well, to pronounce that policy a dramatic mistake:

As time went on, American policymakers increasingly presumed that as China became more prosperous, it would open up, it would become freer at home, and indeed present less of a threat abroad, it’d be friendlier. It all seemed, I am sure, so inevitable. But that age of inevitability is over. The kind of engagement we have been pursuing has not brought the kind of change inside of China that President Nixon had hoped to induce.

This puts the end of the decades long engagement. ‘Engagement is dead’.

But is it?

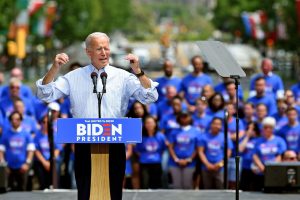

Image Credit: Erin Schaff/The New York Times

So, the

So, the

So to restart our Global Summitry podcast series for the new roaring ’20s – the ‘Now’, the ‘Summit Dialogue’ and the ‘Shaking the Global Order’ series, I had connected with my good colleague Tom Wright from Brookings. Tom is the director of the

So to restart our Global Summitry podcast series for the new roaring ’20s – the ‘Now’, the ‘Summit Dialogue’ and the ‘Shaking the Global Order’ series, I had connected with my good colleague Tom Wright from Brookings. Tom is the director of the